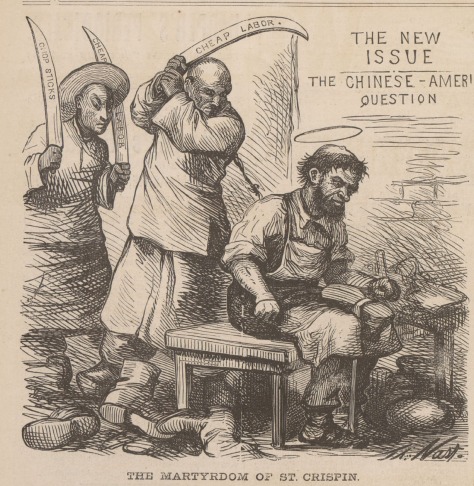

This cartoon, published on July 16, 1870, is one of the more curious of Nast’s Chinese pieces. The cartoon addresses the issue of using Chinese labor as an efficient, lower cost alternative, thus blurring the definition of contract, or forced slave labor known as “coolie” labor. For a nation still coming to terms with the issue of slavery and slave labor, “coolie” labor was viewed as suspect, and a threat to replace free white labor for the betterment of capitalist or business interests. For another perspective click here.

Two Chinese workers stand behind a shoe cobbler. They carry sabers marked “Cheap Labor” on the blades. The cobbler is St. Crispin, the patron saint of leather workers. The cobbler’s hair is styled in a tonsure and a halo hovers over his head. Whether intentional or not, the cobbler bears a strong resemblance to Nast’s hero, Abraham Lincoln. He concentrates on his work and appears to be unaware of his Chinese visitors lurking behind with their swords raised. A violent attack is imminent.

The Chinese man at the far left has an abnormally elongated face and slanted eyes that upturn at an unnatural angle. He clenches two weapons, but he has yet to lunge toward St. Crispin.

At center and directly behind the cobbler is another Chinese man. His facial features are more normal and do not appear exaggerated. His look is intent on what he is about to do. With a two-handed grip, he hurls his “Cheap Labor” blade high over his head, ready to strike the first blow upon cobbler oblivious to the danger.

Nast identifies this as a “New Issue – The Chinese – American Question” and that question is how to reconcile the Chinese into the labor force.

The next issue of Harper’s Weekly reported on an uprising that may have been breaking at the time Nast executed his drawing. In that issue, Harper’s Weekly reported on Mr. Sampson, owner of a New England shoe factory. Experiencing financial difficulties, Sampson sought wage concessions from his factory’s labor force. They agreed to consider his request provided Sampson open his books to make sure the owner had done all he could and operated his business above board. Sampson refused this request and instead arranged to recruit Chinese workers from San Francisco. The article makes an explicit distinction that Sampson recruited Chinese workers already in the U.S., unlike that of an individual by the distinctive name of Mr. Koopmanschoop, a labor broker, and capitalist who dealt directly with China for his labor force. The article infers that the methods to import Chinese labor from China were nothing more than disguised slavery. Coolie labor became a subject of everyday discussion and concern, but Harper’s argues, Mr. Sampson was well within his rights to seek out cheaper labor to save his business.

The Harper’s Weekly article takes a favorable view of the Chinese workers. “Since their arrival…their deportment has been excellent, and the prejudice at first existing against them is said to be gradually giving away” (Harper’s Weekly, 23 July 1870). The article included two large illustrations, not drawn by Nast, showing where the factory was situated, and an interior scene of Chinese men working inside the factory without incident. The scene was clean, peaceful and unremarkable.

Presumably, as news of Chinese workers entering American factories in New England reached New Yorkers, Nast quickly created this small cartoon, placed near the back of the issue in the advertisement section. Cartoons of this size, roughly 5 inches by 5 inches, were typically nestled near the advertisements. This section of the magazine may have been blocked out, ready to receive a quick image for breaking news. This would explain why there is no article in the paper about Chinese shoemakers that week, but appeared in the next issue.

The pro-capitalist position of Harper’s Weekly does not describe the Chinese as strike breakers, but according to John Kuo Wei Tchen, this maneuver in Massachusetts and a similar one in New Jersey was a deliberate attempt to break a strike of the shoe labor union known as the Knights of St. Crispin. “The Crispins were one of the largest trade unions in the country, claiming some forty thousand members in Massachusetts alone.” Using Chinese labor in such a manner made national news, and reinforced the perception of the Chinese as cheap, possibly indentured or forced labor. Willingly or not, by undercutting the price of white labor, and working to the satisfaction of employers, the manipulation of Chinese labor played a crucial role in how their racial identities were formed within a Euro-centric America (Tchen 175-176).

As a Radical Republican, Nast believed in the capitalist point of view that saw a benefit by adding Chinese labor to any given industry. Yet, Nast drew an unflattering portrait of Chinese labor with this cartoon. As John Kuo Wei Tchen notes, “Chinese cheap labor” had become a “war cry” and that was reflected in cartoons and in contemporary poetry, such as Bret Harte’s “Plain Language from Truthful James.” The poem depicts a Chinese character, Ah Sin, as a cunning heathen. Nast would revive Ah Sin nine years later, but this 1870 cartoon reflects the idea infused in the poem that allowing the Chinese to have “unfettered entry” into America was dangerous (Tchen 196). Nast would also play on the poem’s title with his pro-Chinese cartoon “Blaine Language” one of many cartoons which criticized U.S. Senator James G. Blaine for his anti-Chinese positions.

Whether Nast believed in the danger or merely reflected what was discussed on the street—as a topic for conversation— is unknown. The cartoon is inconsistent with the majority of his Chinese cartoons. The figures, however, closely resemble the Chinese men who taunt Denis Kearney in Nast’s 1880 cartoon, Ides of March.

Historian John Kuo Wei Tchen speculates that Nast likely did not have any real knowledge or exposure to the Chinese in New York, and adds that his cartoons “indicate familiarity with the representational conventions of Chinese in literature and on stage, but not much other knowledge” (211). Tchen’s assessment makes sense. The question remains, does that excuse Nast from drawing images like this – or was characterizations like this one purposeful because Nast was simply incorporating the popular view?

Related to this cartoon: See “The Latest Edition of “Shoo Fly“” and “The Chinese Question.”