Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was an illustrator and cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly from 1857 (1862 full-time) to 1887. In his 30-year career with the magazine, Nast drew approximately 2,250 cartoons.

When Nast died in 1902, the New York Times eulogized him as the “Father of American Political Cartoon,” an honorific bestowed in no small part for his scathing political caricatures of William M. Tweed, who ran New York City’s Democratic political machine at Tammany Hall.

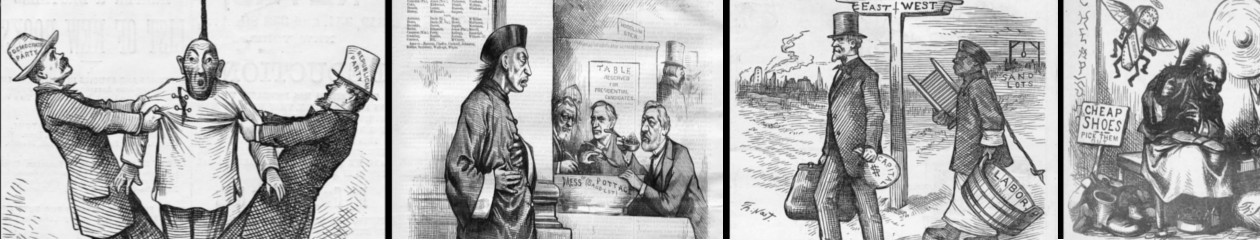

Nast is widely credited with exposing Tweed’s corruption, and Nast’s Tweed cartoons comprise the vast majority of scholarship about the artist and his work. It is from this visually enriched, scandal-ridden time period that journalism historian Thomas Leonard described as an era of “visual thinking.” Beyond the printed word, in cartoons, readers could see facts, suggest truths, and form opinions.

During the Tweed era, Nast began the first of 46 cartoons about Chinese immigrants, Chinese Americans, and China-U.S. relations as subjects or themes for his cartoons.

Seen as a whole, Nast’s 46 Chinese drawings align with Harper’s Weekly editorial position of inclusion and tolerance for all immigrants. Most historians, including Nast scholars Morton Keller, John Adler, and Fiona Deans Halloran, among many, have defined Nast as a pro-minority and, therefore, a pro-Chinese artist. Few disagree that Nast contributed a rare, positive voice for Chinese American immigrants – setting him apart from the work of his peers. Consider, for example, the works of George F. Keller, cartoonist for The San Francisco Illustrated Wasp, an illustrated weekly magazine of “commentary and satire” (West). Keller often took cruel aim at the Chinese by exaggerating physical and cultural differences.

Very little academic scrutiny focuses on Nast’s Chinese cartoons. The most comprehensive thus far, albeit a brief 15-page examination, is offered by historian John Kuo Wei Tchen, who concedes Nast’s overall sympathetic treatment of the Chinese in America. But Tchen correctly points out some grave inconsistencies where Nast lapses into negative Chinese stereotypes. Tchen speculates that “Nast’s exposure to living and breathing Chinese and other racial groups was probably quite limited” (211). It is unknown if Nast ever met or associated with a Chinese person in New York. Reportedly only 200 Chinese were in New York in 1870 – or how he felt about them. Tchen suggests Nast represented what he knew or was told about the Chinese, rather than from direct personal knowledge.

Indeed, this would explain some of Nast’s unflattering images of the Chinese. From 1868 to 1886, Nast’s positive imagery toward the Chinese Americans ebbed and flowed. What is apparent is that Nast relished having a good villain to caricature, and where oppression and persecution of Chinese Americans were concerned, the ire in his ink easily pointed its nib to the Irish.

Was Nast more motivated against those who attacked the Chinese, e.g., the Irish (and politician James G. Blaine), than he was for presenting a case on behalf of the Chinese Americans as individuals? There is considerable evidence to assume that is the case. Given his progressive, Radical Republican philosophy, many of Nast’s artistic choices are indeed confusing.

For example, Nast, a passionate abolitionist, offered the public a stirring portrayal of African Americans with “Emancipation of Negroes” drawn to shine the spotlight on the normalcy and assimilation of newly freed African Americans. A Chinese equivalent does not exist. Regarding the visual treatment of the Chinese in America, Nast did better than most in his profession. But, it is fair to ask why Nast did not more strongly advocate for the Chinese and refuse to repeat stereotypes. But as a nationally prominent cartoonist, his cutting, visual contributions, however flawed, succeeded in drawing national attention to post-Civil War anti-Chinese attitudes emerging as a political and moral issue.

The paths of the Irish and Chinese immigrants in America often intersected. Nast paid attention to the significant conflicts between the two ethnic groups. When evaluating Nast’s treatment of the Chinese, a close examination of Nast and Irish Americans is warranted. Nast clearly saw the commonalities between the Irish and Chinese and their less-than-enthusiastic reception in America. In fact, Nast’s cause de célèbre exposed unfair oppression among all ethnicities and immigrants. When it came to unveiling the root of anti-Chinese sentiment, Nast identified the Irish as the lead oppressors.

Thomas Nast turned his attention toward “The Chinese Question” both as a cartoon title and for the common title of a much larger national discussion that surrounded labor competition. When Nast could link local anti-Chinese sentiment to Tweed and the Irish and their identity as Democrats, Nast was an effective advocate.

Chinese Americans arrived at the Pacific coast of the U.S. in response to the Gold Rush of 1848. “Nearly all the immigrants who came to America were from the province of Canton.” The promise of riches propelled the Chinese to leave grim conditions in China that were both natural and man-made (Sorti 3). Like other immigrants, they came to America for a better life or the promise of economic opportunities.

Resistance to the Chinese presence by white miners, many of whom were immigrants, was immediate. They initiated a string of local laws aimed at delegitimizing Chinese miners and undermining any success the Chinese newcomers might seek to gain in America. Despite these hurdles and acts of violence to drive the Chinese out of Western communities, the Chinese continued to arrive, encouraged by employment opportunities in agriculture and railroad construction, and compelled to flee from poor economic conditions in their homeland.

Lenore Metrick-Chen described the conditions in China at the time as “dire,” resulting from famine and poverty and decades of war with the West–in particular, the Opium War with Great Britain (6). Demonizing the Chinese through visual art became an effective means of setting them apart from other immigrant groups, effectively defining the Chinese as alien, transient sojourners or as “others.”

The official campaign to exclude the Chinese as a race accelerated in the 1870s when an economic recession in the United States heightened labor competition, culminating in acts of violence by white laborers in Western states demanding that “The Chinese Must Go.” Cartoons helped make the argument to deny naturalization to the Chinese.

A battery of specialized laws targeting Chinese immigrants quickly evolved. For a post-Civil War nation emerging from a culture of African American slavery, Chinese laborers in America quickly became suspect and incorrectly classified as forced labor – referred to as “coolies” and temporary visitors known as “sojourners” with no desire to assimilate.

A national discussion percolated. “The Chinese Question,” which began and proliferated along the West Coast and eventually spanned across the U.S., asked Americans, in part, if the Chinese belonged.

Anti-Chinese activists, the most well-known of whom was the Irish-born American immigrant Denis Kearney, repeatedly stoked Sinophobic attitudes and organized white labor against the Chinese. His Sand Lot chants were reinforced with news coverage and imagery which depicted the Chinese as a people who endangered an American way of life.

Defined as coolie slave laborers, carriers of diseases, and non-Christian “heathens,” Kearney and his followers warned that Chinese culture included opium smoking, rat eating and an inherent refusal to assimilate to American culture. In 1882, America answered the Chinese Question. The Chinese Exclusion Act, introduced several times in the late 1870s, finally became law, the only U.S. immigration legislation in existence that banned a race of people from coming to America.

Nast paid attention to the proposed legislation and as talk of exclusion gained traction, Nast responded with some of his most passionate cartoons. Echoing his zeal against Tweed, Nast fixated on Republican James G. Blaine, a charismatic leader of his party and presidential hopeful. Courting the California vote, Blaine sided against the Chinese, and Nast relished his role in reminding the public of Blaine’s hypocrisy.

Fully aware of Nast’s leadership role in Tweed’s downfall, Blaine appealed to the artist and his editor at Harper’s, George Curtis, to cease producing the cartoons. Nast’s pen would not be silenced. His cartoons played a role in Blaine’s unsuccessful presidential bids in 1876, 1880 and 1884. Blaine’s last attempt went as far as earning the Republican nomination. Blaine’s 1884 campaign, two years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, propelled both Nast and Harper’s Weekly General Editor George W. Curtis, to endorse the Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland. It was a startling departure from Nast’s beloved Party of Lincoln. Although Nast’s excoriation of Blaine cost the politician the presidency, Nast’s move to the Democratic side, albeit on moral grounds, significantly contributed to the artist’s loss of favor with his Republican base and marked the start of his downward trajectory at Harper’s Weekly.

By 1892, 110,000 Chinese were in the United States (Pfaelzer). Nast expressed many views through his art. His attitudes on immigration and racial politics contributed to a larger discussion of “belonging” among America’s newest residents and how they were included in the national narrative. How did his status as a German immigrant factor in his depiction of other immigrants and minorities? Can his use of symbols and stereotypes be justified within the genre of cartoon satire? Did the technological limitations of his craft influence the repetition of these stereotypes?

Nast and Harper’s Weekly

Nast began his professional career at the age of 15. He apprenticed at several publications, honing both his artistic talent and a growing acceptance of Protestant doctrine.

In a weekly news magazine format, the current news could be delivered and accompanied by images. Photographs, however, could not be reproduced quickly as they can today—the week between publishing dates did allow photographs to be converted to steel plates for engraving (West). With multiple images, weekly illustrated magazines, unlike dailies, grew in popularity and complemented text-bound breaking news.

At Harper’s Weekly, illustrations and cartoons, including Nast’s, were often drawn directly on woodblock (usually boxwood) or transferred from paper to a cross-cut section of woodblock, carved by engravers and set together with movable type on a printing press. Illustrations were drawn to scale, in reverse (known as relief printing). In relief printing, the areas not receiving ink — the white areas —are meticulously carved out by a staff of engravers, leaving only the black lines in relief to press against the page.

Watch a MOMA expert describe woodcut engraving. * See end note.

In New York City, the most notable weeklies were Frank Leslie’s Illustrated News, the New York Illustrated News, and Harper’s Weekly, the latter being the most respected and prominent. In covering events “disastrous, tragic, or splendid, the visual element could substantially enhance the power of the written word” (Halloran 22). Nast had worked for them all — and in that order — but happily achieved his goal of working full-time at Harper’s Weekly in 1862 (Paine 28).

Harper’s Weekly and Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, (or Harper’s Monthly) were part of a much larger publishing empire known as Harper and Brothers, owned and managed by four brothers, James, John, Joseph ,Wesley and Fletcher Harper. Harper’s Weekly fell under the supervision of Fletcher Harper. As a publishing entity, the family empire “published books from American and European authors on a regular basis”(Halloran 21) as well as school textbooks.

Harper and Brothers enjoyed a national reach and the highest influence among New York City’s publishers. Among the city’s plethora of competitive weekly periodicals, Harper’s Weekly soon took the lead in feeding an “increasing appetite of Americans for news, entertainment, and literature” (Halloran 21). Harper’s Weekly tagline was “The Journal of Civilization,” and its breadth of topics included local and national news, editorials, book excerpts, depictions of Civil War battles, arrivals of immigrants, politics, religion, biographies, political opinion, travel arts and culture both foreign and domestic.

As a freshman illustrator, Nast covered harbor arrivals and fires in New York City. Assigned to cover the Civil War, Nast’s art matured, and his popularity grew. He passionately advocated for abolition and the emancipation of African Americans and emerged as a stalwart defender of Abraham Lincoln’s Radical Republican policies.

During the mid-1860s, Nast’s illustrations were allegorical and lushly sentimental. After the Civil War, Nast ventured into political caricature and focused on Andrew Johnson’s failed Reconstruction policies, and in this genre of caricature, Nast found his true calling. Henceforth, he rarely took his eye off of local and national politics, lampooning and exposing hypocrisy, corruption or fraud from anyone whom he viewed as antithetical to progressive Republicanism.

In local politics, Nast implicated the Irish and Catholics as key enablers of Tweed’s corruption. Nast took particular exception to the Tweed-Irish-Catholic trio joining forces to interfere with the allocation of public funds in support of Catholic schools at the expense of public schools. Nast’s conviction that Tweed was corrupt, the Catholic Church was greedy and power hungry, and the perception of the Irish’s propensity for mob violence gave noble purpose to his cruel caricatures. Nast’s cartoons were brutal but powerfully delivered. His images of Tweed and the Irish and Roman Catholic Church in America are the most well-known and studied cartoons of Thomas Nast’s oeuvre.

Today, many seeking to explain Nast’s images, particularly those with Irish-Catholic ancestry, often examine his cartoons out of their historical context and through a modern prism of political correctness and intolerance of stereotypes. The interpretations of these images have changed as our collective refusal to tolerate stereotypes has evolved.

On the Internet, an abundance of public commentary exists–a collection of online voices who weigh in regarding Nast’s cartoons, images plucked from their historical context and presented as evidence of Nast’s strong bias against Irish Americans in particular, or on Nast’s inconsistent attitudes toward other minority groups in general.

It is important to view Nast’s progression on this issue. The historical timeline of his cartoons and his biography must be considered when evaluating his views on race. Ansel Adams observed, “A photograph is often looked at, seldom looked into.” The same can be said for any art form, including Nast’s cartoons. Nast’s caricatures and illustrations contain multiple layers and experientially formed opinions. These layers need to be examined.

Nast loaded his cartoons with visual clues: contemporary newsmakers, literary figures, symbolism, and quite often, compelling narrative in the form of posters or placards framing his main subject. To properly analyze a completed Nast cartoon, one must peel back the many ingredients Nast purposefully included. These clues are often overlooked. Understanding these components illuminates the reasons for the ire in Nast’s ink.

* I recommend clicking on the top right option to view the whole video. Don’t let the 8 hours scare you! Advance to the 17:00-minute mark to hear an excellent explanation of how Nast’s cartoons were carved. (A Nast engraving of the Tammany tiger is shown on the wall).

Sources (Please refer to a complete list of cited resources here):

Halloran, Fiona Deans. Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2012

Pfaelzer, Jean. Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans. Random House, New York. 2007. Print.

Tchen, John Kuo Wei. New York before Chinatown: Orientalism and the Shaping of American Culture 1776-1882. The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 1999.

Storti, Craig. Incident at Bitter Creek: The Story of the Rock Springs Chinese Massacre. Iowa State Press. Ames. Iowa. 1991.

Excellent! Worth every word. An educator’s dream tool.

Thank you this Website has helped me so much in my report on Chinese immigrants. I think that it is very important that people know about what was going on during the 1880’s.

Thank you Bella! I appreciate that! I found it fascinating too when I first discovered this part of our history. Good luck on your report!

Hi,

This is virendra from pearson press

i want use your some cartoons image in our book”Pearson social studies” so i want know that there are public domain or need to be clearance these images.

Regards,

Virendra Singh

Hello Virendra,

Images that indicate “Walfred” or “UD Scan” in the caption are in the Public Domain. They are scans I obtained personally from my university library and are not copyrighted. While I appreciate the site being referenced, it is not required. Where I have referenced other sources of images, e.g., The Ohio State University, or Library of Congress, please check with them. My understanding is all of Nast and Wasp cartoons are in the Public Domain, unless the source has a proprietary scan, such as Harp Week does, then permission is needed. These all appear with a Copyright watermark.

Hi Michele,

I felt compelled to leave a small note celebrating your work on Thomas Nast. The excitement your words share through this topic led myself to read it in its entirety. I came across your work while on the UDel website and followed your work- to this. Well executed. Best wishes from a new fan.

Mathematician,

Katherine

Katherine, Thank you so much! How kind of you to write!

Hi,

I would like to know any clearance of permission is required

if I would like to use two cartoon images in my book.

1. the-coming-man-20-may-18811

2. what-shall-we-do-with-our-boys-3-march-1882

To the best of my knowledge, these two images are

not labeled as Walfred/UD scan, as indicated in the Copyright notice.

Thanks.

2017/11/15

Hello, The scans that appear on my website were scanned by me personally from a book I own called the Illustrated San Francisco Wasp written by Richard Samuel West. I contacted Mr. West who stated the images were in the public domain, but nevertheless gave me permission to use the images on my website – I would double-check with them/him, for if you are using them in a book for sale, that might require a different level of permission – (my site as you know is free and I do not have ads, so my use of all images is also fair use under the educational condition) Contact Richard Samuel West through the publisher of the book info@periodyssey.com. I am fine with you using the scans I have created for my website.

Dear Michele,

Thank you for your kind reply and providing valuable information.

I appreciate it very much for your double-checking the clearance of using these two cartoon images. In addition, your kind permission to

use the scans you created in your website is very much appreciated.

Looking forward to receiving the reply from Mr. West.

Thank you again for your kind assistance.

Best regards,

Chirst Chin

You are welcome! Please keep me updated on your book! I would love to see it as I remain very interested in this topic. Michee

Dear Michele,

Thank you for your kind comments. I will let you know if there any progress.

Best regards,

Christ Chin

Nast is often viewed as anti-Irish, but he did not hesitate to take fellow German immigrants to task where appropriate. One of my favorites is his “Throwing down the ladder by which they rose,” where the anti-Chinese “1870s Know-Nothings” are characterized as “President Paddy” and “Vice-President Hans.”

Hello, I was recently gifted a news print by Mr. Nast that appears to be in 1877 according to a date on the back of the cartoon which was from a newspaper. Is there a catalog of his cartoons or more info that could be obtained regarding this particular cartoon?

Hi Carran, Yes, HarpWeek maintains two websites, one harpweek.com is a public site that talks about some of the more popular images and their historical significance. However, what you want is the HarpeWeek digital scans of all issues, organized by date. This is available for free via a school or library. This library of scans does not offer any editorials, but does have all the issues in context, so the date of 1877 would be readily available. Typically there would be an article or essay/editorial that would correspond with the image Nast drew. What does the image depict? Do you know the month or day of the issue.

As a political cartoonist myself,I look to illustrators,such as THOMAS NAST,despite some of his social prejudices,as an example of how to

fight against oppression,and hypocrisy within our political system.

At the moment,I’m looking to find a new gig,working for a few small local newspapers. Who knows? Maybe I might have the same impact he had,to readers,in his day!

– BRYAN GERARD BRIGGS.

Would you mind explaining “his social prejudices”? I only discovered him last year when I was given a copy of his cartoon of the Republican GOP elephant which he coined and was the first to create the mascot.

It is a complicated question, as there is little evidence on how Nast personally thought about people, in a social construct. Nast’s feelings about politics are much more clear. His recent biographer Fiona Deans Halloran has probably addressed this in the most detail. I think we can safely assume that he possessed common beliefs and prejudices of his time – in that different demographics likely saw themselves as “better than” another group, no different than 2nd or 3rd generation Americans, people “born there” or “nativists” looked down upon immigrants in general. As a whole, Germans probably saw themselves more superior than the Irish, given that those Germans who arrived in the city, did so with needed skills, had education and money, where the Irish did not. In U.S. society prior to the Civil Rights era, it is fair to say that most white Americans saw themselves as superior to blacks? Does that mean that every white person felt that way? Nast likely behaved no differently than others in his German community. Luc Sante, who wrote “Low Life” demonstrates that almost every demographic coming into the country shared a spot as the “low life” for some period of time. So in that context, Nast likely felt superior or better than others, but not in a personal sense, and certainly not unique to how others shared and demonstrated social prejudices during this era. Nast is often held up as “Anti-Catholic” which I find odd since he was born into that religion. But politics did infiltrate social constructs. Nast’s beef with the Irish, was particularly focused on their association with Tweed, and then as the driving force within the U.S. Catholic Church which Nast and others felt were overshooting their influence regarding funding of public and private schools. It is only with those issues that he takes out his pen and attacks with stereotypic imagery. But if he ran into a regular Irish person or Chinese person or black person on the street, was he hateful? There is no evidence to indicate he was. His artwork is overwhelming of his championship of the underdog. In his residence in Morristown, N.J., his family employed an Irish domestic worker, as did many, in the same way white families employed black people as domestic, e.g. (The Help). In interviews I conducted, the neighborhood in Morristown was highly populated with Irish and there are no records of conflict. My own personal 75% Irish heritage was the spark that turned my curiosity into research about Nast. “Why did he hate my people?” I asked myself. “Why did others hate the Irish so?” And I didn’t want to have a knee-jerk response and condemn Nast, as others have done with relish, without finding out why. The answer was both complicated and specific. I can say I learned as much about the Irish as I did Nast, and there is blame to go around. Nast was justified in some of his criticisms. And when he resorted to visual attacks, it was almost in all cases, related to a specific incident that he felt was corrupt or unjust. His true feelings about who ought to be welcome in America can be seen in his 1869 “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner” that illustration is the foundation of his social and political views. All were welcome to America’s table. As he matured and aged, and lived in a time of great change and transition, there is no way to know how he personally reacted to people. He was a political animal, and he certainly went after Democrats with relish, particularly how they related to Tweed, the failure of Reconstruction, etc. I do recommend reading Halloran’s book for more insights. She assumes Nast disliked Irish people because most Germans at the time did, so that is fair on one level, but his private, personal views are in the end, largely unknown.

Michele, thank you for that articulate answer to my question. It is very much appreciated. I too am of Irish/Scot decent. My mother was a Duff and My father was a Maxey. I am definitely going to read more on this. Thank you again.

Carran Manning

Hi! My name is Ariane Lee, and I am a junior from Syosset High School. I am participating in the National History Day competition, and have chosen Thomas Nast as my topic. I came across this website, and I would love to conduct an online interview with you about Nast. Would that be possible? If not, I understand. Thanks so much!

Sure! I would be glad to! Email me at walfred@udel.edu and I will send you my phone number and we can pick a time!

Hi, Michele!

For the term “coolie”, I have the following for you.

Coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a pejorative term used by European for unskilled labourer hired for low/subsistence wage, typically those of Chinese, India and other parts of Asian descent. e.g. porter at railway station. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/coolie ; https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/coolie ; https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/coolie