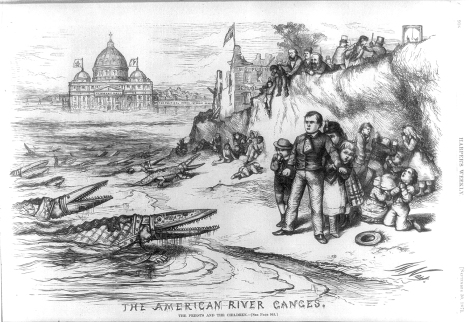

The concern of Roman Catholic interference in public education is brilliantly rendered in what many scholars regard as Nast’s most famous, and well-executed anti-Catholic image. Steeped in fear-mongering invasion imagery, Harper’s Weekly published the image twice. The first, on September 30, 1871, implicated Nast’s nemesis, William M.Tweed, and reprised by popular demand on May 8, 1875, the cartoon shows Tweed absent from the cliff.

The American River Ganges, Harper’s Weekly, September 1871 by Thomas Nast. The original image of Nast’s most famous anti-Catholic image, Tweed was safely out of the picture, literally and figuratively when the image was republished on 8 May 1875 along with other minor modifications. Library of Congress

The American River Ganges, Harper’s Weekly, September 1871 by Thomas Nast. The original image of Nast’s most famous anti-Catholic image, Tweed was safely out of the picture, literally and figuratively when the image was republished on 8 May 1875 along with other minor modifications. Library of CongressThe image is a tour de force of imagination and caricature technique. Nast dehumanized the Catholic bishops by turning them into reptiles. They emerge from the water toward the New York shoreline. Two clergies in the foreground have stereotypic Irish faces.

As if to emphasize the the double meaning of “feast,” slithering out of the water on all fours, are bishops wearing their pretiosas, the ornate, jewel-encrusted mitres worn on Sundays or feast days, the priests are drawn as salivating crocodiles with jaws ready to devour, or feast if you will, on school children. A Protestant minister or teacher, with his Bible, tucked in his waistcoat, and his saucer hat tossed to the ground, stands defiant, guarding several fearful children who are shivering, praying, and cowering as certain death approaches. In the middle of the scene, several bishops arrive on the shore ready to clamp down on defenseless and dispensable non-Catholic students.

A Chinese boy on his hands and knees attempts to flee. Native American and African American children press up against the cliff with nowhere to escape.

Nast shared a Radical Republican, utopian vision which held that public schools should be open to all children, regardless of race, creed or ethnicity, and he drew many images of an idealized public school system that included a diverse student body learning in harmony. With the Catholic initiative to create their own schools, and with the support of public funds to do so underway – funded through Tweed’s influence, Nast feared that separate sectarian schools for each ethnic and racial groups would result. “Nast believed that bringing children together into the public sphere, under democratic control, muted their religious and racial differences and molded a unified, multiethnic [sic]American society” (Justice 174). Tweed and the Roman Catholic Church interfered with that vision.

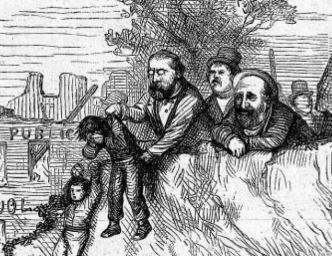

Boss Tweed and his “ring” lower Protestant children from a cliff to be devoured by Catholic bishops

Boss Tweed and his “ring” lower Protestant children from a cliff to be devoured by Catholic bishopsPerched atop the cliff, Tweed, and members of his political machine lower Protestant children to the feeding grounds below. Columbia, Nast’s ever-faithful symbol of American compassion and justice, is bound and led away to a hangman’s gallows.

Nast drew Tammany Hall as an extension of the Vatican in New York City. The flag of an Irish harp and the Roman Catholic papal standard fly in authority over the land. Nast echoed the Republican and Protestant fears that Catholicism was taking over municipal governance

Nast drew Tammany Hall as an extension of the Vatican in New York City. The flag of an Irish harp and the Roman Catholic papal standard fly in authority over the land. Nast echoed the Republican and Protestant fears that Catholicism was taking over municipal governanceAt the center top of the image, a U.S. Public School crumbles. An inverted American flag, a sign of distress, flies prominently. On the other side of the river, stands Vatican- shaped structure named “Tammany Hall.” The cartoon was reissued in 1875 and the sign over the buildings was changed to “Political Roman Catholic Church.” Flags of the Papal Coat of Arms, and the Irish harp fly atop the side domes. Attached to the right of the Roman Catholic Church is the “Political Roman Catholic School.”

In Harper’s Weekly, an essay written by Eugene Lawrence accompanied Nast full-page cartoon. Lawrence, a nativist and frequent contributor to the periodical, blamed the Catholics for the end of the public school system and its aim “to destroy our free schools, and perhaps our free institutions has been for many years the constant aim of the extreme section of the Romish Church.” The essay continues its attack on Jesuits, and the daring aggressive spirit of the ultramontane Irish Catholics who Lawrence claims governs New York. The author also touts brave European governments who have dared to challenge Roman Catholic influence of their schools and other institutions.

The institutions that managed New York Public Schools claimed their schools provided non-sectarian education. Catholics disagreed, noting Protestant-based libraries, textbooks and “the daily reading of the Protestant version of the Bible” in classrooms as an unsatisfactory environment for learning (Heuston 54).

“The establishment of a new state school systems in the United States seemed to substantiate Catholic fears that the attitudes of European secularists were taking root in America” (Heuston 169). Prior to the Civil War, Catholics wanted to participate in the public school system without endangering their faith. Catholics were encouraged to pursue the issue after New York Whig Governor William Seward suggested in 1840 that state aid might be given to Catholic schools (53). Henceforth, New York’s Catholic Church, led by Archbishop John Hughes, began strategies to thwart the new school system by working through their political contacts, but these attempts were unsuccessful. A preoccupation with the Civil War and its aftermath diverted attention from the issue of public education – the issue would not surface again until the close of the 1860s, when Catholics once again picked on the issue and “Republican Party and Catholic Church leaders the late 1860s and early 1870s joined a bitter battle of words over the future of public education” (Justice 171).

Justice suggests the American Public School served as a metaphor for the northern lifestyle; “the public school evoked the small-town Protestant backbone of the Republican Party” (180). In 1869, Tweed as head of Tammany Hall and acting State Senator, “snuck a provision in the annual tax levy bill for the city through the state legislature” which provided 20 percent of the city’s excise tax be earmarked to Catholic schools (Justice 182). Tweed’s crafty maneuver set Republicans to outrage in motion and solidified scrutiny by the Republican-based press, such as The New York Times and Harper’s Weekly. Nast’s crusade against the Catholic interference in the public school system coincided with his attacks on Tweed’s other political malfeasance. His attacks on Tweed tripled Harper’s Weekly circulation (Hess 100).

Nast’s principal opposition to the Catholic Church rested on what he feared was the Church’s aim to subvert the nation’s public school system by diverting public funds to sectarian schools (St. Hill, 70). Benjamin Justice’s research on Nast’s feelings about Catholic interference in the public school system provides valuable insights. Justice feels that American antagonism toward Catholics resulted from the church’s rapid rise due to immigration and the American Catholic church’s adoption of conservative ultramontane Romanish leadership, which “increasingly insisted on separate, publicly-funded schools, making it incompatible with republican government and unfit to offer mass education at public expense” (175). Justice surmises that Nast’s vicious blasts at the public school issue came to life as part of a broader attack on the relationship between Tammany Hall and the Catholic Church. Nast visual attacks were pointed objections to “Catholic political ascendency over the state” rather than an attack on Catholic culture or Catholics as individuals (183).

The image is often used as evidence by Catholics to prove Nast hated Catholics. Nast produced many anti-Catholic images, but all of these Catholic cartoons hover over two issues—The New York Catholic Church’s demand for public funds to create their own sectarian schools (appeals which succeeded due to their alliance with Tweed) and the conservative Catholic (ultramontane) concept or doctrine of papal infallibility, wholly adopted by the New York Catholics.

Blind allegiance to an infallible monarch figure perplexed Protestant Republicans. They viewed American Catholics’ allegiance to the religious figurehead across the ocean as antithetical to American origins which rejected governance through monarchs. As Heuston and others have made clear, the Irish-American’s devotion to a pope was clear evidence to Protestants that American Catholics had no desire to assimilate into American culture and behave as independently-thinking individuals.

Most Protestants misunderstood papal infallibility to mean that Catholics believed that the pope could not err in decision making or judgments. [See Catholic definition] Nast’s family and religious background were likely rooted in a more progressive, reformed Catholicism. Along with most Protestants, Nast could not fathom the blind allegiance that Irish Catholics awarded the Roman pontiff. For Nast American Catholic policies represented a flawed doctrine and philosophy with the potential for extreme abuse.

Nast’s campaign against Catholic interference in public schools equaled if not rivaled his obsession with Tweed. He saw Tweed and the American Catholic Church in New York as symbiotic and co-dependent. This reality particularly rankled Nast, and as a theme for caricature and commentary, one Nast would not relinquish.

I knew the cartoon, but even as a historian of ethnicity I did not realize there were two versions, with and without Tweed. The 1875 rerun coincided with the “Blaine Amendment” which would have put a ban on public funding of religious schools into the Constitution.