A German immigrant to the United States, Thomas Nast (1840-1902) is best known for his illustrations and cartoons that were published in Harper’s Weekly’s Journal of Civilization. Nast is most associated with his depictions of “Boss Tweed” and “Santa Claus” and for his development and popularization of the donkey and elephant as political party symbols. More recently, “bigot” emerges as an identifier, due to a large number of anti-Irish, anti-Catholic cartoons he produced. Painter, illustrator, engraver – it was Nast’s ability to create scathing caricatures and cartoons that quickly elevated him as the leading artist at Harper’s Weekly. After the Tweed series, Harper’s commonly referred to Nast as “Our Special Artist.” Nast’s caricatures, oftentimes brilliantly brutal, did not begin or end with Tweed. Nast used his pen to expose corruption and hypocrisy wherever he saw it – and he saw almost everywhere.

A champion of the underdog, and politically liberal, Nast would nonetheless turn a friend into a villain if he felt they didn’t further the progressive Radical Republicanism he adopted while employed at Harper’s. In New York City, Nast turned his scrutiny on many subjects. His blistering artistic output was controversial in his day. He caused a stir. He also tripled Harper’s circulation.

Photograph of Nast by Napoleon Sarony, taken in Union Square, New York City. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Photograph of Nast by Napoleon Sarony, taken in Union Square, New York City. Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsNast remains controversial today. His largest body of work, created in the post-Civil War era, reflects attitudes that are inconsistent with a more modern sensibility. When his name was placed in nomination for a 2012 induction into New Jersey’s Hall of Fame (Nast moved to Morristown New Jersey in part to escape threats from Tweed sympathizers) a campaign largely waged on the Internet doomed his induction.

I first learned about Nast when I began exploring my family’s genealogy on sites like Ancestry.com. My lineage is 75 percent potato famine Irish, 25 percent Bavarian. Raised in the Roman Catholic faith, if asked, my family identified ourselves as Irish-Catholic, but I grew up thinking we were just “American” like everyone else. I was unaware of the experiences of my immigrant ancestors. Nast was an immigrant also, arriving in the United States in 1846 at the age of six. As Germans, the Nast family joined the second largest wave of immigrants to New York, second only to the Irish.

German immigrants were far less destitute than their Irish counterparts, coming to the United States for both political and economic reasons. Many came to America with marketable skills and formal education. According to Nast’s biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, the Nast family appeared to possess financial means and could make choices on where to live, and where and how to educate their young son in a new community.

Nast was born in the Landau, der Pfalz, in the Rhineland-Palatinate or Rheinland-Pfalz, now a state of modern Germany, bordering France. Nast is often referred to as a Bavarian, and although his hometown was historically linked to Bavaria, the region was considered autonomous in the Nast’s family lifetime, as it is now.

Nast was baptized a Catholic in Germany and there are suggestions the family practiced a progressive form of the faith. In America, Bigelow, his biographer, suggests he was sent to Catholic schools, where he did not thrive. Bigelow paints Nast as a poor student, and how or if his Catholic instruction factored into that is unclear, yet his familial Catholicism is an interesting subtext, particularly as he is often accused of being anti-Catholic.

For one of my earliest graduate courses, American Art and Culture in Context, each student was assigned to select an artist to represent each century of American history and determine the cultural context in which it was created and why it was significant. I decided to narrow my focus to a particular genre, political/editorial cartoons, and selected Benjamin Franklin as artist for the eighteenth, Thomas Nast for the nineteenth, and Patrick Oliphant for the twentieth century. My interest in political art and Thomas Nast intensified.

The Usual Way of Doing Things, by Thomas Nast, 1871. Source: The Ohio State University

The Usual Way of Doing Things, by Thomas Nast, 1871. Source: The Ohio State UniversityIn 2011, I enrolled in a graduate course, Contemporary Culture: Asian American Immigration, taught by Dr. Jean Pfaelzer, author of the book Driven Out, an account of the prejudice and legislation against the Chinese immigrant in America—my first introduction to a period of American history with which I had little familiarity.

Chinese Americans have the particular distinction of being the only race of people ever to be officially excluded from American citizenship. From their arrival as gold miners in 1848, mistrust grew to intolerance and anti-Chinese hysteria and violence proliferated. Anti-Chinese depictions in trading cards, postcards and in magazines, greatly shaped American attitudes against the Chinese. Cartoons helped to demonize and firmly define Chinese Americans as “others.”

My research for this course studied the techniques used to demonize, or in rare cases defend, Chinese Americans. To represent the anti-Chinese cartoons, I researched the San Francisco Illustrated Wasp artist George Frederick Keller and compared his work to the Chinese cartoons published by Nast at Harper’s. During Nast’s lifetime, a negligible number of Chinese resided in New York City. Estimates ranging from 90 to as many as 200, in the 1870s. It is impossible to know what personal interactions, if any, Nast had with the Chinese Americans, yet he drew 46 cartoons depicting them. Nast’s Chinese cartoons are generally accepted as sympathetic to the Chinese and Nast makes a case for the rest of America to accept them. Could Nast have made a stronger argument? Nast made some interesting artistic choices.

His Chinese drawings display a wide range of characteristics —and not always dignified. Nast’s pro-Chinese drawings really come to life when the Chinese are threatened by the Irish (often Nast’s key players in the white labor movement) and when political figures, such as Republican presidential candidate James G. Blaine, shifted from a declared position of tolerance and inclusion and sided with anti-Chinese factions and worked to pass the Chinese Exclusion Act, Nast relished exposing this type of hypocrisy. The ongoing relationship between the Irish and the Chinese did not go unnoticed by Nast.

Given my heritage, I claim a right to be as upset as any Irish descendant regarding his treatment of Irish Americans. It is disconcerting to see my ancestors depicted as apes. The simian stereotype originated in Great Britain and migrated to the United States where it continued to surface in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and thrived in the aftermath of the Great Famine and massive Irish emigration to North America.

Obviously, a multitude of factors beyond an inherited prejudice was at work here. What motivated Thomas Nast to draw such images? Nast did not invent this stereotype, but he certainly perpetuated it. The image above, The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things has made many appearances on the Web as an example of Irish defamation. The image is hardly original to Nast; it is almost identical to Sir John Tenniels’s anti-Irish cartoon in Punch. This unflattering cartoon surfaces as one of many to argue Nast’s banishment from the Hall of Fame and brand him as a bigot. The image is usually cropped to remove the story below. It is rarely considered in the context of events (Orangemen’s riots) that compelled Nast to repurpose Tenniel’s cartoon.

The prevailing Protestant view of the Irish as a lower form of humanity was indeed quite common and well-established in the consciousness of everyday Americans long before Nast set foot in New York City as a six-year-old immigrant.

Knobel’s Paddy and the Republic establishes how prevalent anti-Irish sentiment coursed throughout America. Had it not been for the Irish Americans political alliances, which in Nast’s view involved stolen elections and misappropriated public funds, there would be little reasons for Nast to attack the Irish Catholics. His pen turned on anyone, or any group, who he felt had abandoned principles or a moral code.

Everything Nast drew was executed with deep conviction. The question is, were his convictions misplaced? One may not agree with Nast’s conclusions, but those who are informed about his life and times are better judges about where and why Thomas Nast drew his creative inspiration.

Nast’s treatment of the Irish stands apart from his depictions of other immigrants and minority groups. Most historians such as Morton Keller, John Adler, and others concur that Nast was, in most cases, sympathetic to African Americans, Native Americans and in particular, to Chinese Americans. Yet, even as he argued for their fair treatment and inclusion of Americans, he often perpetuated stereotypes and drew unflattering images if he felt members of these communities acted irresponsibly or made questionable alliances. Sentimental and sympathetic depictions of minorities could suddenly shift into cruel caricatures. Politics, rather than racism, was often the integer.

Selecting examples and selective research, therefore, exacerbate what appears as deep inconsistencies in Nast’s art. Was Thomas Nast a racist? A hater? Isolate an image here and there, and the evidence might seem clearly pointed toward the affirmative. This conclusion, however, would be a mistake. To understand Thomas Nast is to understand his experience as a German immigrant in New York City, to appreciate the Radical Republican politics he adopted, and to view his body of work chronologically and within historical context. How did his time, place, and circumstance shape his views? Why does he appear to turn against the Catholic faith of his family? Was his attitude toward Catholicism merely an aversion to the Irish, or the reverse? In what ways should the Irish be held accountable for their own bad press?

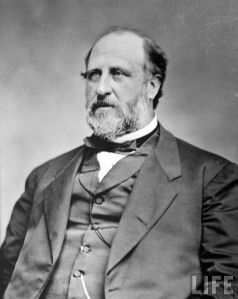

William Meager Tweed photographed in 1870. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

William Meager Tweed photographed in 1870. Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsIn Nast’s world, Irish and Catholics were inexorably intertwined with William Meager Tweed, the Tammany Hall Sachem or “Boss” who ran a corrupt “Ring” in New York City. Tweed was a Scots-Irish Presbyterian, and as a younger man, no admirer of Irish Catholics. All that changed when Tweed quickly figured out the political value of this massive immigrant population.

Tweed cultivated the allegiance of the Irish and the Roman Catholic Church for political benefit. In the view of many at the time, especially for the Republican Protestant ruling elite,* of which Nast belonged. Tweed arranged votes for favors — a malodorous quid pro quo, That the Irish allowed themselves to courted by Tweed, and how the Roman Catholic Church in New York City grew and influenced public funding, lie at the heart of Nast’s the ire in his ink.

*Until the great Irish famine migration poured into the United States, the vast majority of Americans were white, Euro-centric and Protestant. Protestant Americans were the elite ruling class and self-proclaimed gatekeepers into America.