The Chinese Question by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, February 18, 1871

The Chinese Question by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, February 18, 1871If one studies any number of Thomas Nast images, it won’t be very long before one encounters Columbia, the classically draped female figure that Nast favored as a symbol to personify America.

She was not a Nast invention.

Cartoonists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries used male and female symbols to represent their nation’s government and principles. In the same tradition as Great Britain’s John Bull and Britannia, cartoonists like Nast employed the male figure of Uncle Sam to represent the United States government and the motherly, nurturing Columbia to embody the “motherland” to remind audiences of America’s values and democratic promise.

Unlike their male counterparts, these national female representations were typically fashioned as Greek or Roman goddesses. Nast is sometimes erroneously credited with inventing Uncle Sam. He did not. Uncle Sam was an outgrowth of Brother Jonathan, the American version of John Bull. Nast can be credited with helping to make these images part of the visual vocabulary of his time, frequent ingredients in his commentary on hypocrisy and corruption. Please double click on any image to view a larger size.

America was first personified during the Revolutionary War in a poem by a recently-freed African American slave Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784). In her poem, To His Excellency General Washington (1776) Wheatley writes in part:

Fix’d are the eyes of nations on the scales/For in their hopes Columbia’s arm prevails.

Well-versed in classical literature, Wheatley’s Columbia was “an invented goddess who lent a tinge of classical refinement to the nation building project” (Gruez 542-53).

Cartoon historian Donald Dewey suggests that Columbia was an outgrowth of Minerva, the Greek goddess of war. “Minerva morphed into Columbia during the Revolutionary War” when she replaced Britannia as a symbol on ship mastheads and various business enterprises (13). Columbia occasionally appears in British cartoon illustrations in the nineteenth century, where she continues as a classical goddess alongside her relatives Hibernia (Ireland) and Britannia (England). These women stand, cheer, weep, protect and champion their respective country’s highest values and most valiant patriots. They often appear in scenes of conflict to mediate or stand fearlessly as a barrier to danger or injustice. All appear in issues of Punch, England’s leading weekly illustrated magazine a magazine whose artists influenced Nast (Paine 28).

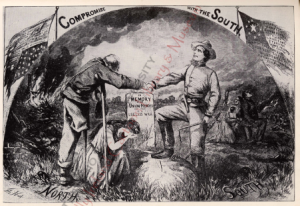

Columbia made her first appearance by Nast near the close of the Civil War on February 6, 1864. Columbia Decorating Grant a double page spread that honored the efforts of the Civil War’s Union General U.S. Grant. But it was Compromise with the South, released in the heat of Lincoln’s reelection bid that Nast’s biographer Albert Bigelow Paine wrote: “that stirred the Nation more than any picture hitherto published” (98).

Compromise with the South, Sept 3, 1864, by Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly. Source: The Ohio State University

Compromise with the South, Sept 3, 1864, by Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly. Source: The Ohio State University“Nast represented the defiant Southerner clasping hands with the crippled Northern soldier over the grave of Union heroes fallen in a useless war. Columbia is bowed in sorrow, and in the background is a negro family, again in chains. The success of the picture was startling. An increased edition of the weekly was printed to supply the demand, and the plate was used for a campaign document of which millions of copies were circulated” (98).

The image’s intent was to rally emotion for Lincoln. Republicans shared a high level of concern that Lincoln would not win reelection and that the Civil War had come at too high a cost to the Union, here seen capitulating to the South. The Union flag is upside down, an image of distress, a symbol Nast would often employ. A Confederate soldier stands erect, proud and defiant, with one boot upon a broken Union sword. A severely wounded Union soldier hangs his head in submission. He is faceless. Union cities are burning on the left, African Americans on the right, remain in bondage. Columbia has center stage, a woman, the giver of life, weeping over a mounded grave, over the bodies of her Union sons who died in a “useless war.”

Lincoln won reelection but was assassinated soon after his second term. As the nation grieved, Nast brought out the one figure who could encapsulate and represent the national sorrow and grief.

Columbia speaks for a country in mourning. Columbia assumes center stage under circumstances of deep emotion. Her face hidden, she nonetheless captures the empathy of a collected grief. Her whiteness and purity stand in stark contrast to the darkness engulfed by Lincoln’s coffin. The somber images of a Union Army and Navy soldier, flank the image, left and right respectively. Columbia is distraught, yet she is pure. She is surrounded by flickers of light and close to the glowing name of her hero, Lincoln.

When the Civil War concluded in favor of the Union, it fell to the Andrew Johnson administration to carry out the promises of Reconstruction and Emancipation of freed African American slaves.

And under this administration, Columbia would soon surface again, and this time she was not hiding her face.

Two images appeared side by side in the August 5, 1865, issue of Harper’s Weekly. They were titled “Pardon and Franchise.” The images, Paine writes, “struck firmly the most strident note of the Reconstruction discord.”

Columbia sits in a position of authority, deciding whether to pardon the leaders of the southern cause, confederates, and secessionists. She appears bored by their entreaties for a pardon. Columbia is not sold on their change of heart, she is not confident of their declaration of good intent. And why should she accord them the consideration and reapplication for membership in the Union, when these same men cannot extend the same equity to an African-American amputee Union veteran? (In Nast’s early career at Harper’s, his work was very sympathetic to African Americans.Later, this view changed after they had won the right to vote, and aligned with the Democratic Party, the party that originally had fought against abolition. Nast was disturbed by this turn of events and exasperated, began to draw African Americans in less-than-flattering caricatures).

And not this man? Columbia argues for Civil Rights for a wounded African American veteran. Harper’s Weekly, August 5, 1865. Library of Congress

And not this man? Columbia argues for Civil Rights for a wounded African American veteran. Harper’s Weekly, August 5, 1865. Library of CongressNote the difference in Columbia’s posture. She rises to greet the African American. She shares the same stage, the same level as the beleaguered veteran. Her right hand touches the man’s soldier. Her other hand opens in his direction. Columbia bears no weapons because she does not fear this man. She stands on the marble landing and presents him as he makes his entry hobbling on an elaborate, oriental carpet.

Nast’s Columbia does not suffer fools lightly. She weighs all arguments, she advocates justice and fairness for all Americans, regardless of their race, creed, or station.

Columbia is often drawn strong and determined. According to John Adler, Nast used his wife Sarah as the model for Columbia’s face. But Columbia’s facial expressions and carriage could vary widely. When angry, Columbia was a force of nature. She stood erect and tall. Her facial features gently chiseled, with an almost masculine quality. Her nose Romanesque, her eyes usually fixed,and her expression resolute. Like the country she represented, she could display a full range of emotions and temporary vulnerability which mirrored her nation’s pulse or sentiment. She would wear a variety of hats, tiaras or crowns, literally and figuratively.

Nast would sometimes refer to her as Lady Liberty, long before Bartholdi’s statue was erected. Often she wore a tiara, emblazoned with US or NYC, depending on the focus of the cartoon’s issue. The status of her headgear is important, as it usually contains a message. In the case of the Tammany Tiger is Loose, (featured below) her tiara has fallen and broken. Columbia and her relatives Justice and Liberty often hold a sword or a whip, but sometimes all these figures needs is a clenched hand to get their point across.

As Nast’s work for Harper’s Weekly moved from engraved illustrations to the wit, sarcasm and lampooning of his caricatures, Columbia often occupied an important place in Nast’s black and white panorama. Nast placed her in everyday situations so that his readers could relate to her moral message. Columbia is by turns seen as a housewife, cleaning up messes, or as a school teacher, dismayed by the state of public schools. She is often portrayed as weeping for the tragic turns her nation would delicately navigate. For Nast, Columbia was a ballast of sanity and righteousness against the ridiculousness in his images. As Nast’s depictions and caricatures would increasingly favor the comic or ironic, his inclusion of Columbia would impart the seriousness of his message. Whenever Nast felt compelled to call out a wrong, he often chose to have Columbia by his side.

As a symbol, Columbia would lose favor to a new incarnation, Lady Liberty, influenced by the great copper statue designed by Frederic Bartholdi. In other instances, Columbia’s style and grace sometimes assumed the more specific role of Justice, Peace, Law or New York City. Whatever their name, their maternal, nurturing presence consistently delivered a message of hope and integrity- their inclusion always meant as a reminder to higher values, toleration, fairness and democratic principles of inclusion. Nast’s catalog of Columbia is impressive. He includes Columbia in many key situations. Consider the voice she represents. What crime, hypocrisy, injustice, unfairness is she commenting on?

Tammany Tiger Loose November 11, 1871, Harper’s Weekly. One of the rare images of Columbia as a victim, being torn to shreds by the corrupt Tammany Tiger, as Boss Tweed and his Ring look on. Source: The Ohio State University

Tammany Tiger Loose November 11, 1871, Harper’s Weekly. One of the rare images of Columbia as a victim, being torn to shreds by the corrupt Tammany Tiger, as Boss Tweed and his Ring look on. Source: The Ohio State UniversityThe Tammany Tiger Loose is a rare exception that shows Columbia as a victim. The tiger, Nast symbol of Tweed’s ferocious power, cares little for Columbia. She is in his way. Tweed and the Tammany Ring watch with satisfaction as their instrument of power tears American values apart.

In, “Let the good work (housecleaning) go on,” December 16, 1871, a domestic Columbia is a symbol of “every woman” at least a nineteenth-century version, prepares to clean America’s (or New York City’s ) house after the villains have left.

2020 is a prime time for Columbia to be resurrected in our collective consciousness! Is there someone who can rise to the occasion and do that?