The queue (pronounced cue) was a distinctive hairstyle of the Jürchen-Manchurian or Manchu tribes who occupied the northeast region of what is now modern China. In the early part of the seventeenth century Manchu general Nurhaci demanded that all males who surrendered to his victorious army “must imitate Jürchen practice and shave the fronts of their foreheads and braid their hair into a long pigtail or “queue,”” (Spence 29).

By the mid-seventeenth century, the Manchus ushered in the Qing Dynasty and dominated the major cities of China. The Ming Dynasty disintegrated. To successfully rule China, the Manchus adopted many Chinese practices, but the hairstyle was not one of them. The new Manchu rulers insisted that the Chinese adopt the Manchu style of dress and hairstyle. By 1645 the mandate read that “every Chinese man must shave his forehead and begin to grow the queue within ten days or face execution.” The queue hairstyle remained a key to identification of soldiers in battle.

Therefore in their native homeland, the queue was both a military necessity and a symbol of submission to Qing rule.

Few Chinese women were permitted entry into the United States. For Americans, Chinese men were the only representation of Chinese people and the queue added to the perception that the Chinese men were unnatural. Most Americans could not help but notice the queue.

Male populations dominated the gold mines of California, Chinese men, along with white miners, “did their own domestic work – they cooked, sewed and washed their own clothes.” Along with their long pajama-like tunics and long hair, “Chinese men were depicted as lacking virility. In this mostly male world, Chinese men became targets of white men’s fears of homosexuality or the objects of their desire” (Pfaelzer 13).

A few Chinese men, particularly the early Chinese in New York, behaved as mandarins, adopting western dress and “intermarrying with neighboring Irish women” and contributed to a “creolized community” (Meagher). Most western Chinese retained the Manchu identification. In visual art Chinese “otherness” focused on their flowing native clothing, eye shape, diet and overall American perception of facial features as exotic. Of particular fascination was the queue – a key and central marker in visual art representations of the Chinese. In New York City, the traditional hairstyle had become a problem, “their queues were constantly the target of pranks by white boys and men,” (Tchen 83).

By 1856, the New York Times estimated 150 Chinese in New York City. Tchen notes, “the more assimilated these men appeared–equipped with a Western name and some knowledge of standard English–the more access to the dominat cultuure they could gain,” (Tchen 85). Combined with thier “adoption of Anglo-American names–like the marriages to Irishwomen and the establishment of families–signaled that many of these Chinese intended to stay,” (Tchen 86).

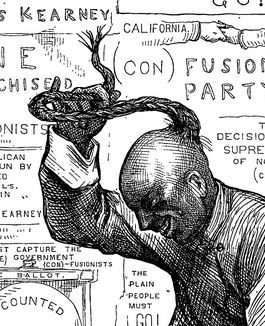

But Nast’s Chinese always wore the queue hairstyle. They are often frayed at the base of the neck and almost always braided. Nast used queues in a number of ways: as a weapon for the Chinese, a weapon against the Chinese, as a tool, as a barometer of emotion, as a lifeline, as a hangman’s noose, as a tail, and on Americans as a symbol of irony.

As John Kuo Wei Tchen has noted, Nast likely did not possess first hand personal experience with Chinese people in New York. If he had, he likely would have encountered a Mandarin Chinese who assimilated to western culture, learned the English language, invested in real estate, adopted western style and behaviors including inter-racial marriage (often with Irish women). Nast’s reliance on the queue affirms Tchen’s suggestion that Nast’s knowledge of the Chinese people was “representational” rather than experiential.