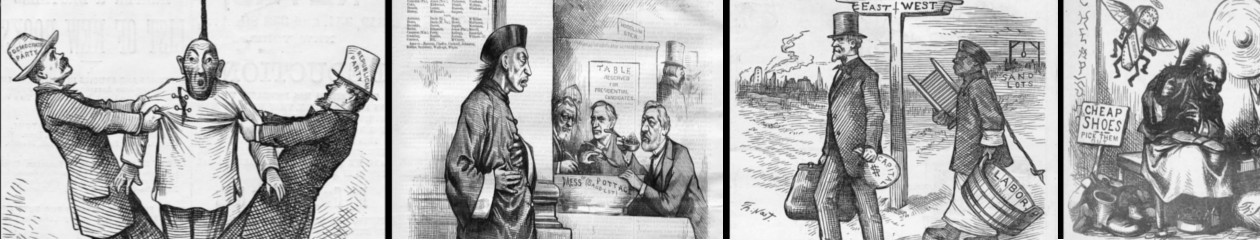

Double click image to enlarge. Click the plus sign to enlarge further!

“A Diplomatic (Chinese) Design Presented to the U.S. – 12 February 1881 by Thomas Nast, for Harper’s Weekly. Source: Scan at UDel by Walfred. Public domain

“A Diplomatic (Chinese) Design Presented to the U.S. – 12 February 1881 by Thomas Nast, for Harper’s Weekly. Source: Scan at UDel by Walfred. Public domain

This highly detailed full-page wood engraving appeared in Harper’s Weekly without an accompanying article.

In the cartoon a Chinese dragon curls around a Chinoiserie vase—it drops a document “New Treaty” from its claws into the neck of the vase. The vase is highly ornate – its style familiar to fashionable American households that collected Chinese art and porcelains (Chinoiserie) to display as a statement of cultural sophistication.

The vase is also cracked. The fracture is serious, running from under the dragon’s tail to the base of the porcelain, where it bifurcates into another fracture. At first glance, the dragon, who Nast has drawn with a devilish grin, appears to be possessive of the vase, but it might be trying to hold the vase together with its body and tail—and the offering of a negotiated concession—as an incentive to stay together. Under the dragon’s left claw reads “diplomacy.” The dragon is dark, menacing, and both protective and defensive of its territory and history in dealing with western culture.

The treaty Nast refers to is the 1880 Angell Treaty – a modification to the Burlingame Treaty negotiated by Rutherford B. Hayes. Bending to the will of anti-Chinese hysteria in California, China agreed to American limitations on Chinese immigration on the promise that the United States will not try to trade opium in Chinese ports.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, China enjoyed an advantaged position between itself and England. England wanted the advantage neutralized or eliminated and began to forcibly import opium into China. In Collecting Objects/ Excluding People, Lenore Metrick-Chen sums up the consequences of the opium trade and its relevance to the U.S.

When the Qing government protested this illegal activity, Britain used its military to force the trade’s continuation. The Opium Wars resulted in huge financial, military, cultural and humanitarian losses for China. Poverty forced many people, mainly young men, to risk the truly wretched conditions of the ocean journey to America. (6)

Harper’s Weekly commented on the treaty in response to an apparent snide editorial originating out of England. Harper’s justified the terms of the new treaty, which ironically continued to award China “most favored nation” status, and reflected on the possible prohibition of Chinese immigrants as being good if it kept the U.S. from forcing opium on the Chinese as the British had done. Harper’s went on record earlier and speculated that “The friendly acquiescence in the restriction of immigration should at once satisfy the California apprehension” (Harper’s Weekly Jan. 29, 1881) which of course the treaty did not.

An aftermath of the Opium Wars was the damage it did to American opinions on all things Chinese. Chinese works of art, once prized by cultured Americans, began to lose their luster in American homes, and American began to favor Japanese objects. “For a short time in the 1870s, Americans began to look enthusiastically at both Chinese and Japanese things, but as the decade drew on approval voiced for Chinese things diminished” (Metrick-Chen 37).

In Nast’s image the caption reads that the artist sketched the vase from a private viewing in Washington D.C. Upon the neck of the vase, Nast has drawn the U.S. Capitol, and, the U.S. Flag upside down, a symbol of distress. A single shamrock replaces the flag’s stars, an indicator that Nast continued to feel the Irish had too much power and influence in American governance. An eagle bearing “85” on its shield (the significance of that number cannot be determined) hovers over the Capitol dome. A string that appears to be kite ties, crosses the throat of the vase. Under the neck of the dragon, Nast includes two Chinese men who dangle from nooses created from their queues, They hang under a sign that reads “Rum Hole.” A fire smolders with “Washington Herbs.” The herbs indicate a ritual or ceremony accompanied the hangings.

In the center, representing England, is a portly John Bull. Bull has fallen off his steed. The horse escapes to the left. Bull wears a “St. George’s” medallion. Big Ben can be seen in the background. The face of the famous clock is Chinese. John Bull bears the scars of other diplomatic mishaps. His right leg is in a cast, adorned with shamrocks and a harp, both symbols Nast used to represent Ireland.

At the vase’s base, a semi-circle frame labeled “Opium Business” is affected by the fracture. Two Chinese men are stoned by the product they are forced to sell. To the right a ship carrying “opium” arrives ashore.

Nast also addressed the new treaty in the Feb.5th issue with his cartoon “Celestial.”

He included a similar vase in the 1882 cartoon “The Veto.