Politicians paid attention, particularly those with presidential ambitions. They were willing to sup at the anti-Chinese stew.

With an energy matched only by his anti-Tweed campaign, Thomas Nast went after Republican presidential hopeful James G. Blaine, then serving as U.S. Senator from Maine, for siding with Kearney and his cause. Nast targeted Blaine repeatedly. Relentlessly.

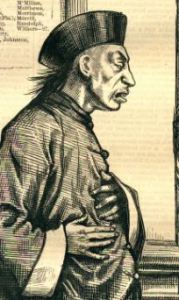

In this full-page cartoon, a Chinese merchant or diplomat has stopped at the entry of “Kearney’s Senatorial Restaurant.” There, Blaine, along with other politicians dines at a “Table Reserved for Presidential Candidates” and eats from “A Mess of Sand-Lot Pottage.” Blaine scoops up a heaping spoonful of Kearney’s sandy stew, the sight of which sickens the merchant as he grabs his hands to his stomach in disgust. A sign hovers over the inner wall, “Hoodlum Stew.”

Above and to the left of the Chinese merchant, Nast has listed the names of politicians who voted “yeah” and “nay” and those who abstained. Nast wishes to fully expose those responsible for the injustices done to the Chinese.

In the same issue, George W. Curtis condemned the Chinese Bill in the strongest terms

It is long since the country has been stirred with so genuine an indignation as that produced by the passage of the Chinese Bill. It was so wanton a breach of the faith of treaties, so gross a wrong, committed with such haste, and without a pretense of the necessity of haste, that the popular condemnation was immediate and universal.

Curtis went on to admonish the breaking of a treaty (Burlingame Treaty) that had been entered in good faith. He applauded the President Hayes’ veto of the bill and decried those who sought to abrogate the longstanding legislation.

Interestingly, Nast’s representative of the Chinese people, depicted in this cartoon, is not attractive. He does not possess the round, kindly face seen in Civilization of Blaine and other cartoons. This figure looks tired, aged and drawn, and as intended, sickly. One could argue a sinister quality. He is not as sympathetic or approachable as other Nast “John Chinaman” characters, and perhaps less likely to elicit an empathetic response from Nast’s audience as a result.