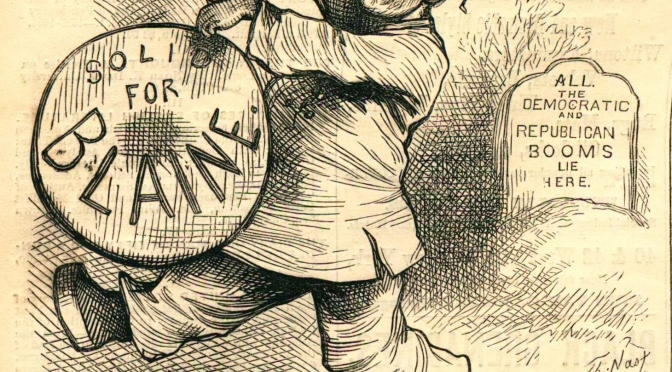

Like the year before, 1880 was not a good one for presidential hopeful James G. Blaine. Thomas Nast went after the Republican senator from Maine with a visual vengeance. Nast broke his allegiance with his beloved party of Lincoln, and took on Blaine with a relish comparable to his attacks on William. M. Tweed more than a decade earlier.

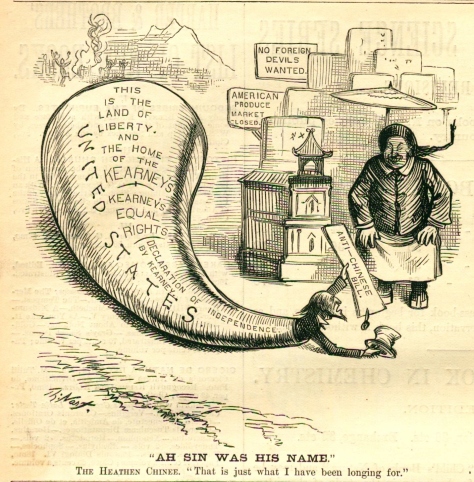

Blaine aspired for national office. He sought to win votes in California and made a decision to break from his party and earn votes by siding with anti-Chinese Denis Kearney and the Workingmen party. Kearney’s war cry, most notably delivered in vacant Sand Lots, coined the phrase “The Chinese Must Go” which he delivered with charismatic zeal before and after each speech.

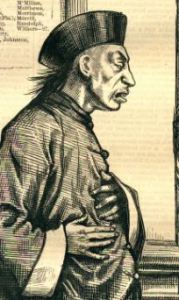

In this alternative reality cartoon, it is the Chinese who demand that Kearney, and his supporter from Maine leave. The Chinese figure is confident and defiant and taunts Blaine behind his back. He removes his hat to expose his shaven head, except for the braided queue grown from his crown. He dangles the braid toward Blaine, who doesn’t appear to know quite what to make the behavior. Chinese were typically thought to be docile, but this Chinese man feels emboldened to lash out at the august senator. Blaine’s expression is not one of appreciation.

On February 14, Blaine is reported to have been asked, “Ought we to exclude them?” His reply: “The question lies in my mind thus: either the Anglo-Saxon race will possess the Pacific slope or the Mongolians will possess it” (qtd. Gyory).

Nast taunts his nemesis as well with the visual question, how does it feel to have done to you what is being done to the Chinese?

The Chinese man craves an answer to the same question. He wants Blaine to experience what it feels like to be an outcast and to be excluded. The Chinese were legally prohibited from becoming citizens and could not vote. Nast identifies the Chinese man as a”Non Voter” who exclaims: “Now Melican Man know muchee how it is himself.”

Above the Chinese man’s head, a sign shows a trans-Atlantic handshake between Democrats in California and Republicans (led by Blaine) in Maine. The handshake is a fusion of interests and with Maine breaking with the Republican Party, a change in immigration policy.

This sign, as well as top banner, plays on the word “fusion.” Nast adds the preface “con” to indicate the tumult his Republican Party is experiencing.

Another sign reads, “Denis Kearney is ready to lead a gang of men to Maine, to make the Republicans GO.” Although Blaine clearly jumped the Republican ship on the Chinese issue, Kearney had not converted the rest of the Republican Party. The signs on the wall warn Republicans that with Kearney in control, and along with the Chinese, the Republicans were next on his Exclusion list. Blaine, hat in hand, is appealing to stay. With his break in philosophy, the Chinese see Blaine as a traitor.

In California, Republicans sided with the capital interests of labor and soon fell out of favor once Kearney began his campaign to oust the Chinese. Kearney and the Democratic Party soon dominated California politics, and politics there clearly fixated on removing the Chinese.

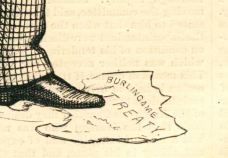

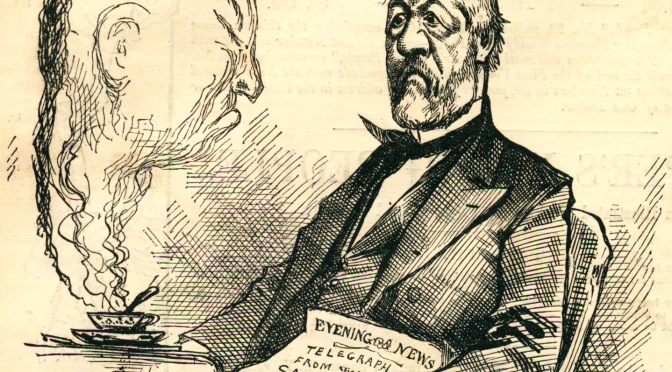

Harper’s editorials had previously lamented the abrogation of the treaties and Blaine’s role in the treaty’s demise and decried that presidential politics had trumped common sense:

CONGRESS has announced to the world that the United States intend to break treaties at their pleasure. The peremptory abrogation of the Chinese treaty is a flagrant breach of public faith which sullies the good name of the country, and puts every other nation upon its guard in under-taking any dealings with us which depend upon our honor… But to argue that the presence of a hundred and ten or twenty thousand Chinese upon the Pacific coast is such an imminent peril to American society and civilization as to justify the peremptory abrogation of a treaty, without notice or attempted friendly modification, is insulting to common-sense. (Harper’s Weekly, March 30, 1879).

Additional reading: Andrew Gyory, “Don’t think Trump will ever pass a Muslim Exclusion Act? Just ask Sen. James G. Blaine,” The Washington Post, December 8, 2015