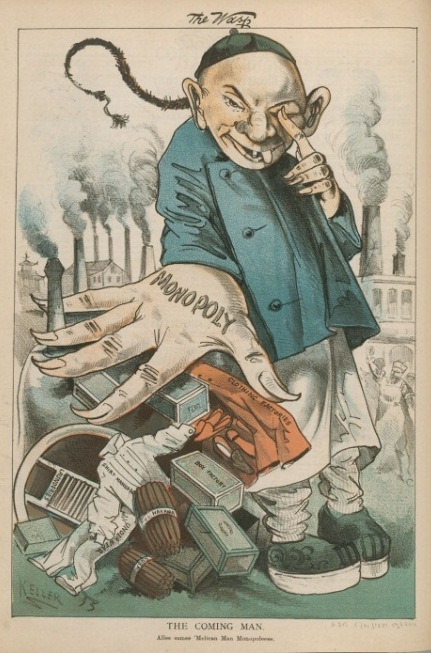

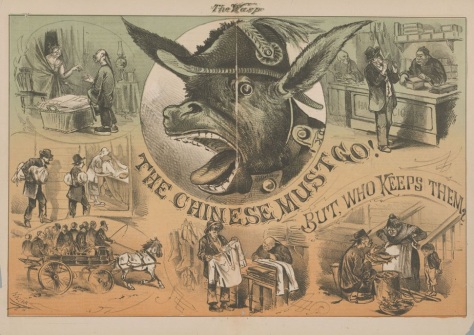

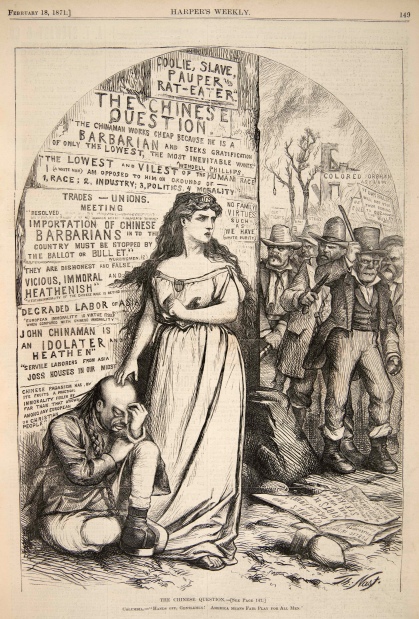

“The Chinese Question” by Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly. Feb. 2, 1871, Source: Walfred scan

“The Chinese Question” by Thomas Nast for Harper’s Weekly. Feb. 2, 1871, Source: Walfred scanThe Chinese Question is full-page cartoon published in Harper’s Weekly, February 18, 1871,

Nast believed in tolerance of all races, nationalities, and creeds. He was not, however, tolerant of ignorance. He deplored the mob mentality which, in his mind, the Irish represented and embodied. Their alliance with Tweed and Democratic Party values drove Nast to draw with savage fervor. It wasn’t the Irish per se, but what the Irish did with their growing political power and alliances that Nast found disturbing. As Patricia Hills points out, “he [Nast] castigates only the ignorant and bigoted who engage in reprehensible deeds” (115).

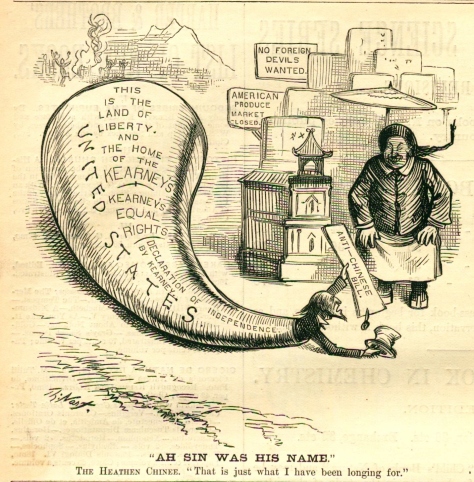

Unfortunately for the Chinese, the Irish played a major role in Sinophobic hysteria. In her book Driven Out, Jean Pfaelzer quotes a New York Times article on the role of the Irish against the Chinese:

It was well known that the chief objection to the Chinese in California comes from the Irish. It was from this class that the Democratic Party used to draw most of the political capital which it gained by fostering the prejudices against the Negro. Fleeing to this country, as they claimed, to escape British oppression, the Irish immigrant always made haste to join the ranks of the oppressors here. They voted, almost to a man, with the Democratic Party…now that slavery is abolished, we find them in the front ranks of the haters and persecutors of the Chinese. (52-53)

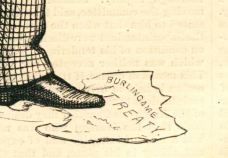

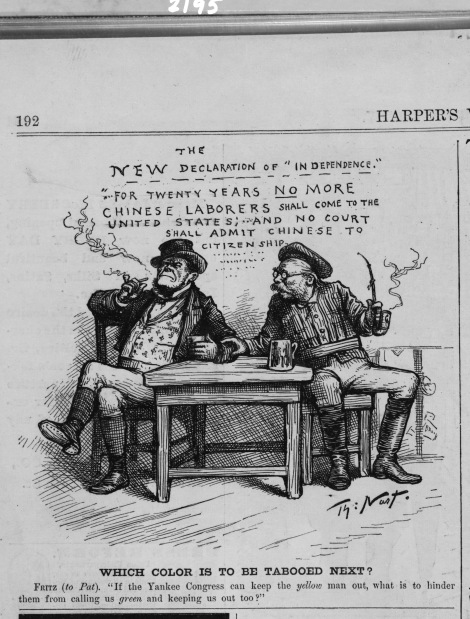

Accompanying this cartoon was a short, but powerful Harper’s editorial, “The Heathen Chinee” which decried the fear-mongering and blame placed upon the Chinese for labor displacement. In a bid to strengthen his Irish constituency, Tweed sought to restrict the use of Chinese railroad labor through legislative means. While a state senator, Tweed sponsored a bill to prevent the Chinese from being hired on projects. Although Chinese population in New York was statistically minute, estimated to be only 200 individuals at the time, Tweed favored invasion vernacular to stoke fear within the predominantly male, Caucasian workforce. Harper’s Weekly’s editors observed,

The working-men of this State know perfectly well that no such danger exists as that which is hinted at in Mr. Tweed’s bill. The Chinese invasion, of which he seems to be so much afraid is altogether mythical, as everybody in his sober senses is well aware; and Mr. Tweed presumes too much on the ignorance or the prejudices of the working-men if he expects to delude them with such a flimsy cheat. The general sentiment of the American people on this question is admirably expressed in Mr. Nast’s cartoon. A majority in this country still adhere to the old Revolutionary doctrine that all men are free and equal before the law, and possess inalienable rights which even Mr. Tweed is bound to respect.

Nast featured an imaginary local brouhaha in his cartoon The Chinese Question.

In the cartoon, Nast places an angry, defiant Columbia front and center to confront the Workingmen menace. As she does in all Nast’s cartoons, Columbia serves as a reminder of America’s values. She stands over a crouched and defeated Chinese man. In addition, Nast utilizes what would become a favorite technique — to plaster current controversy on a wall of public protest. On the wall all the various forms of hate speech spouted against the Chinese could be read and considered.

Chinese are in kind referred to as “coolies,” “slaves,” “paupers,” and “rat eaters.” Rat eaters, in particular, became a favorite and virulent Chinese stereotype deployed to great effect, especially on the West Coast. The posters exclaim and dehumanize the Chinese and affirm their “otherness.” “Barbarians” and “heathens” are additional descriptive terms prominently displayed. The placards pronounce the Chinese as the “lowest and vilest of human race,” “vicious and immoral” declares another. Nast’s wall is an effective tool. It collects the hate speech used and witnessed within the local white labor community and regurgitates it into a printed form, giving it additional legitimacy. Each layer of verbal expression collects and builds like within a pressure cooker. Workingmen would stop at no insult to rid themselves of the emerging Chinese menace and threat. The Chinese must go. “Their importation must be stopped.” Nast plastered the street dialogue – the prejudice for all to see their collective ugly truth and consider the lie.

Nast created a clear visual divide on the issue. The hard edge on the right separates Columbia and the Chinese man from the trouble that is arriving from the other side. Columbia’s body stands in the path as a violent mob approaches. The vertical division creates a tension and a theatrical suspense against what comes next and who might prevail.

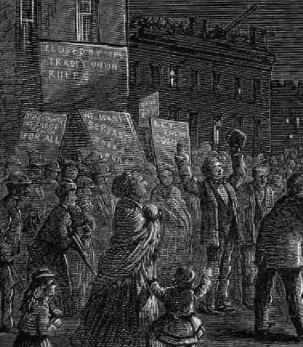

Whipped up by the Tammany frenzy is New York’s version of the Workingmen’s Party. Led by Nast’s quintessential brawny Irish leader, the mob angrily turn the corner toward Columbia and the Chinese target. Nast dresses his thugs as would-be gentlemen. His Irish brute wears a waistcoat and top hat. The high fashion does not change his savage character or propensity for violence.

Nast’s Irish brute

Nast’s Irish bruteWell-dressed as he may be, his face betrays his brutality. His features are roughly chiseled, his steely glare focuses on the impending attack. He brandishes a club in one hand and a rock in the other. This Irish ringleader is eager for some good old-fashioned mob violence. Behind him, four other men are visible, and by their normal faces, not all are Irish. All are white and possess guns or weapons and expressions of anger. Behind them, faceless mob members carry signs in the air. One sign reads, “If our ballot will not stop them coming to our country, the bullet must.”

Nast reprises imagery from the notorious New York 1863 Draft Riot to recreate a scene in 1871 and give it additional implications. Nast drew original 1863 eye-witness drawings of the New York City draft riots and at the time, did not overly implicated the Irish in the violence at the time. Eight years later, he rethinks his position. By including 1863 draft riot imagery to this event, Nast links Irish involvement with racial violence. In the background lies the evidence of their most notorious mob activity–the lynching and destruction of a “colored” community.

The Orangemen’s Riots followed later that summer on July 11-12, 1871 and Nast would once again deploy the same lynching imagery against the Irish. During the same riot, a colored orphanage burned to the ground. By including a smoldering orphan asylum in the background, Nast indicates this mob and associates the participants to that crime. A barren tree is seen in the distance. An empty hangman’s noose dangles from a leafless tree. Below, makeshift tombstones acknowledge buried rights, blood, and strikes. With the African American issue handled and put in their rightful place — in graves, the Irish-led mob now turns its eyes to the Chinese question. One problem down, one more problem to go.

Nast’s audience understood the significance of Columbia’s inclusion. She appears in Nast’s cartoons with great effect and is a formidable, if not heroic challenger to thwart Tweed. Having fought and won many battles, she alone has the wherewithal to protect an emotionally defeated Chinese man. Columbia is a veteran of these battles. Slumped against a wall, framed by “heathen,” “idolater,” and exclamations of paganism, he is confused and helpless against this onslaught of white terror and oppression. He raises one knee to support a clutched hand and lowered head. His eyes are closed and his expression is one of utter despair. Columbia’s long tresses toss as she turns her head, alerted to the approaching mob. Her tiara is marked “U.S.” Her right hand gently touches the head of the crouched Chinese man. Columbia’s left hand rises above her waist and over her heart into a fist. Her neckline bears a shield of America’s stars and stripes. Her expression is resolute. She will not stand for what is about to go down. She addresses the mob, “Hands off, gentlemen! America means fair play for all men.” Columbia is Nast’s voice.

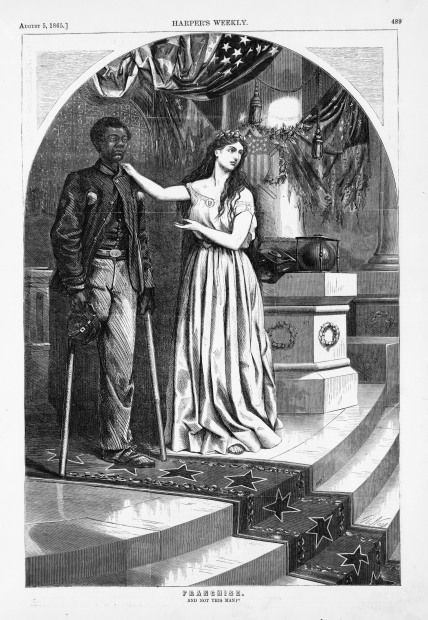

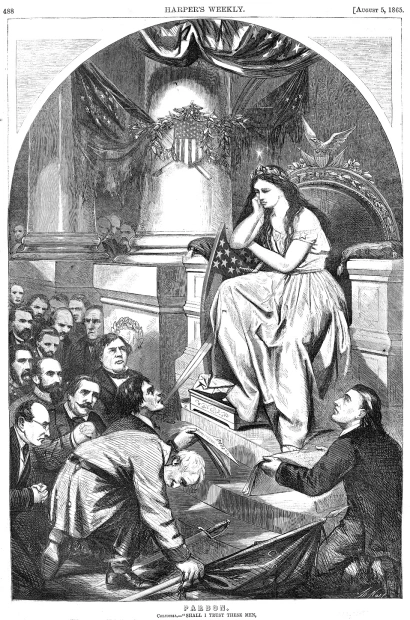

Columbia defended the downtrodden before. Consider how Nast uses her for “And Not This Man?” on August 5, 1865.

And not this man? Columbia argues for Civil Rights for a wounded African American veteran. Harper’s Weekly, August 5, 1859. Library of Congress

And not this man? Columbia argues for Civil Rights for a wounded African American veteran. Harper’s Weekly, August 5, 1859. Library of CongressHere, as in the Chinese Question, Columbia advocates for civil rights, this time for a wounded African American Civil War veteran. Although seriously wounded, he stands erect. He possesses a quiet and embattled dignity. Columbia touches him at the shoulder and invites him to step up for consideration for acceptance as an American. She is speaking to his legislative detractors who appear on an accompanying page.

In Nast’s Chinese Question, Columbia touches the head of the Chinese man. Although he Is able-bodied, he cannot stand on his two legs, he is unable to face his accusers as a whole man, even with Columbia by his side.

Nast has intentionally weakened the Chinese man in the face of the mob, and for viewers, the question is why. Is it to evoke empathy for the Chinese man or is it to make the mob look despicable ? Could Nast have drawn the Chinese with more dignity? The Irish were afraid of labor competition. Struggling to get established in America, the Irish organized in their new country and resolved that they would not suffer the oppression they experienced in their former Ireland. As Timothy Meagher noted, the Irish had no history of prejudice or exhibited any racist behavior in Ireland. They possessed, Meagher suggests, all of the sensitivities necessary to be empathetic to others who were oppressed. But in nineteenth-century Ireland, the Irish had learned that organization and activism produced results, albeit limited.

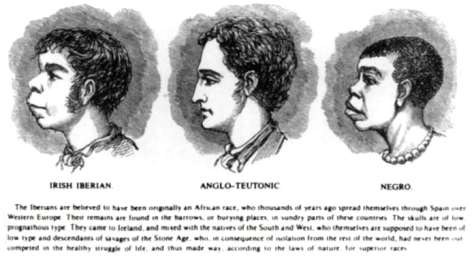

The new Irish immigrant in America faced hurdles other immigrants, such as the Germans did not. During the Great Famine, the Irish arrived in very large numbers and in the most destitute of conditions. As Roman Catholics, they were considered by the dominant Protestant population as members of a strange cult, unwilling to assimilate to American culture. These built-in prejudices, Meagher argues, forced the Irish to assert their “whiteness” and be demonstratively aggressive to other races, in particular, African Americans and Chinese Americans. Meagher cites the work of Moses Rischin who observed that Irish Catholics who aligned against the Chinese in California, and Irish Catholics who aligned with Democratic anti-abolitionists in the South, found greater acceptance into the white Protestant mainstream of their respective communities if they joined others who expressed racial paranoia.

The prevailing view of many historians asserts that the Irish feared any form of labor competition. The banding together of White against Black would not work to the Irish’s favor in the Northeast, and Meagher offers several opinions that dispute a view that the Irish were afraid of southern Blacks seeking northern jobs. Meagher warns against drawing such simplistic conclusions that point strictly at racial tensions or only that only targeted African Americans.

The Irish were hostile to all competitors including other ethnicities. They fought with Germans and Chinese. Real fear existed that a “powerful Republican Party and rich industrialists, would overpower the Irish” (223). Meagher notes that the New York Times was exasperated with the Irish, writing in 1880, “the hospitable and generous Irishman has almost no friendship for any race but his own. As laborer and politician, he detests the Italian. Between him and the German-American citizen, there is a great gulf fixed…but the most naturalized thing for the Americanized Irishman is to drive out all other foreigners, whatever may be their religious tenets” (223). Observations such as these, Meagher suggests, establish that tensions went beyond Irish-African-American tension and violence. The Chinese were easy targets.

As victims of the English oppression and prejudice in their homeland, and again in America, and as targets of nativist and Protestant fears in America, the Irish directed their paranoia and distrust toward non-Irish and non-Catholics. Irish Americans battled persistent and ill-informed scientific theory which classified them as a unique and inferior human race.

The Irish were not considered white, at least not culturally, by many Protestant Americans. For Irish-Americans, defining others as inferior was an early step in self-preservation. As other ethnicities began to fear the Chinese, many Irish not only latched on to this common concern but took the lead in ridding the nation of the menace. By attacking the Chinese, the Irish could prove their cultural”whiteness” and earn a legitimate place in American society. Once severely oppressed in Ireland, and again in America, many Irish turned the tables by becoming the oppressors. Nast would never let the Irish forget this irony.