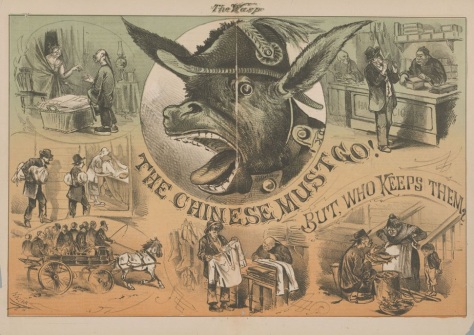

The Chinese Must Go, But Who Keeps Them? was drawn by George F. Keller and published on May 11, 1878. The cartoon is The Wasp’s interpretation of the Workingmen’s Party’s rallying cry against Chinese presence in California. Front and center is a donkey in military garb, an indication of a war- war against the Chinese, and liberal immigration policies. On the epaulets of the donkey’s uniform, the initials “D.K.” represent the faction’s self-styled military leader, Irish-born Denis Kearney and chief crier of “the Chinese Must Go” mantra. Kearney, a charismatic Irish American “began his infamous outdoor “Sandlot” meetings on vacant lots…and understood how to turn rage about unemployment, the price of food, and the huge land grants to the railroads against the Chinese” (Pfaelzer 77).

The cartoon’s title question has a double meaning. Kearney and his Workingmen’s Party were clear on one goal. They wanted the Chinese out of California- out of the West Coast – out of the labor market. Go back to China, go East – as long as they went. They cared little about who would take care of the Chinese afterward.

The title challenges the readers to look within. Who was taking care of the Chinese in California? Who was keeping them, enabling them, to stay in California? The Wasp pointed the finger at their readers.

Surrounding the braying Kearney, six vignettes show the consequences of white citizens patronizing Chinese business; a cigar shop, shoe cobbler, laundry, horse livery and meat butcher. All professions that the Chinese successfully established and sustained through white patronage. White dollars kept the Chinese in place. By asking, “But who keeps them?” the cartoon places the blame directly upon white households. The editorial called for widespread boycotts of Chinese goods and services.

White woman in California were reluctant to give up the freedoms they had enjoyed by subbing out the domestic work to Chinese businesses. “Their freedom to travel east, to visit friends and family, and their time for church and artistic clubs – all the result of inexpensive Chinese servants – was in jeopardy” (Pfaelzer 66).

As the 1873 economic collapse persisted well into 1876, anti-Chinese zealotry organized into groups, such as the Supreme Order of the Caucasians, who vowed to “annihilate” white people who did not follow their “hit list” of boycotts (Pfaelzer 67).

However, the image is not entirely flattering to Irish-born Kearney and his followers. According to Richard Samuel West, The Wasp abhorred mob violence and the paper adopted the editorial position that while it believed in the true threat of Chinese labor at the expense of white labor, Kearney’s method lacked dignity. Unlike Nast who drew Kearney’s realistically, The Wasp rarely used Kearney’s face in their magazines and in this particular instance, preferred to use the Democratic donkey in his place. “The animal appealed to illustrators for its jackass connotations” (Dewey 17).

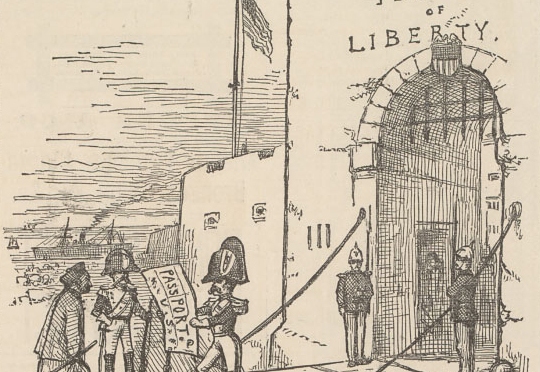

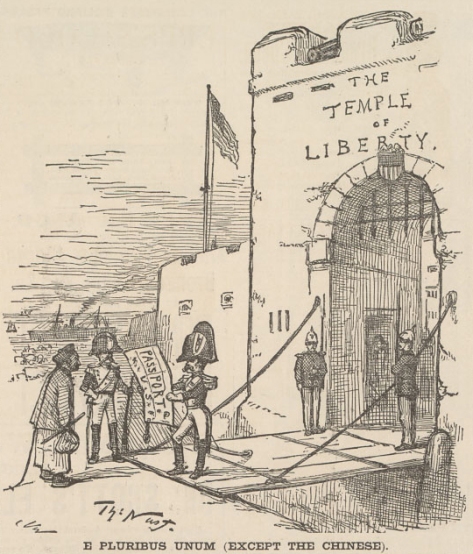

Nevertheless, Kearney’s Sandlot speeches resonated with California Democrats and the working class who comprised Kearney’s Workingmen’s Party. “Just two years later, the new party managed to rewrite local anti-Chinese codes into the second California constitution” (Pfaelzer 78-79). Other anti-Chinese measures would follow in California, and loomed on the federal horizon. Back east, Thomas Nast took notice as he watched the Democratic Party gain influence over the electorate and contribute to the shifting public policy against the Chinese. To Nast’s horror, Republicans came under the influence, as well.

Nast drew numerous cartoons sympathetic to the Chinese’s plight in America. Many of his cartoons react to unfolding events in California. Nast included many references to Kearney in his cartoons, often sarcastically quoting him on wall posters. See example: Every Dog (No Distinction of Color) Has His Day, February 8, 1879.

It should be noted that Keller’s donkey wears a bicorn military hat. A few of Nast’s anti-Chinese cartoon figures contain a military figure wearing a bicorn hat. This may or may not serve as a symbol for Kearney. In the context of Nast’s cartoons, the suggestion seems plausible.