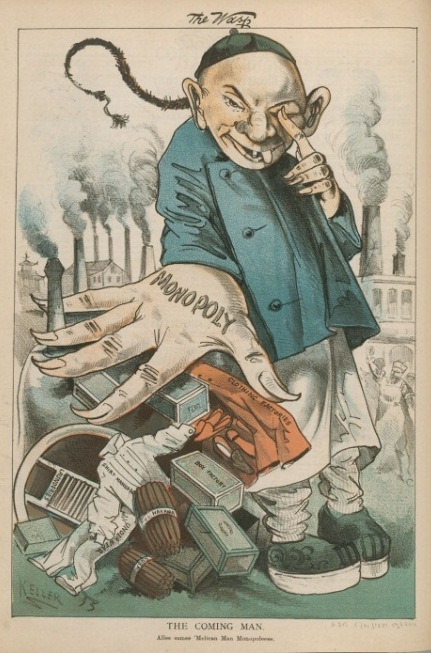

This commanding cartoon was published by The San Francisco Wasp approximately one year before the Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted on May 6, 1882.

The image appealed to white workingmen’s fears of a Chinese takeover of American society and enterprise. Despite the Chinese only occupying 0.002 percent of the population, visual depictions of the Chinese continued to reinforce imagery of infestation and sinister monopolization of industry.

The Coming Man colorfully illustrates the worst in negative stereotyping and Sinophobia. The Chinese man’s over-sized left hand stretches out to the foreground of the image. It is stamped “MONOPOLY” and his fingernails are represented as animal talons, the nails are curled and grow upward like an overhang of a pagoda.

The hand grasps control over trades and services for which the Chinese were most associated – cigar making and sales, laundry, underwear and shirt manufacturing, box factories, clothing, and shoes.

Above his blue mandarin jacket (Chinese tunics were commonly blue, purple or black) is the image of a Chinese nightmare for white Americans. The Chinese man’s face is grotesquely distorted and he greets the viewer head-on with a sinister expression. As if to focus better on those looking upon him, he closes one eye with his index finger to sharpen his stare. His right eye and brow lurch up at an unnatural angle. His ears and nose are large. A devious smile reveals a single tooth, evidence of his bad health. His tongue dangles from the left side of his mouth.

On his shaven head is a skull cap. From the back of his head, the Chinese queue appears to have a life of its own, and whips out from behind the head. The very end of the hair queue looks like the end of a whip.

This Chinese man is not afraid of the white workingman clientele and readers of The Wasp. Behind him and to the left, six factories smolder with industry, possibly a reference to the Chinese Six Companies, an organization which advocated for the Chinese in America. A Chinese pagoda is seen among the buildings. On the right, a few angry, white, Euro-centric workers appear, faintly drawn. They are disappearing. A bearded man wears an apron and a white hat and holds his fist up in the air. Only two factories are viable on this side of the image.

The dominant colors of the cartoon are red, white and blue. This Chinese Man, this “coming man” has taken over the American Dream. He has pushed American workers into the background.

The implicit message of the cartoon is to stoke fear and uncertainty. This man and others like him must be stopped from coming.

The caption reads “Alee samee ‘Melican Man Monopoleeee”