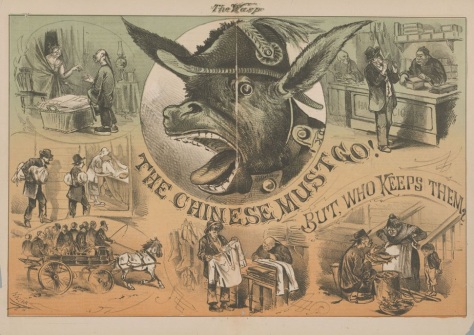

The Wasp’s first anti-Chinese cartoon, The Equal of Persons Gibson and Loomis, appeared on November 18, 1877, six months after the paper opened for business. It was a “caustic response” to Reverends Gibson and Loomis who offered positive testimony to the “good character” of the Chinese immigrant in April 1876 before the Committee of the Senate of the State of California. The committee was a legislative body that held hearings on the social, moral and political effect of Chinese immigration[1] (West 128: Internet Archive). They were part of a San Francisco press that “lambasted pro-immigration ministers as hypocrites” (Paddison 527).

The month-long hearing’s purpose debated the effects of Chinese immigration and sought to determine if the Chinese “advanced or hindered “Christian civilization.”” Most of the testimony was stacked against the Chinese. Foregone conclusions were accepted as fact. The Rev. Otis Gibson, along with Presbyterian Augustus W. Loomis and a few other Protestant ministers testified on behalf of the Chinese asserting that the Chinese “would pose no danger.” The reverends staunchly believed that the anti-Chinese agitation in the community was stoked not by race, but by religion and blamed Irish Catholics [2] as the active agents in the unrest (Paddison 524).

The Reverend Otis Gibson, in particular, was well known as San Francisco’s “most outspoken white defender of the Chinese” (Paddison 522).

Keller’s four-part drawing confronts the witnesses’ pro-Chinese testimony with images of Chinese engaged in unseemly activities. In the top left panel, Keller includes a Chinese male with an ax who chases after a female – a scene of violence to counter the assertion that “they are peaceful.” Top right, three malnourished Chinese men dine in squalid, decrepit living conditions – an exception to the statement “they are clean.” Bottom left, to disavow the claim “they are honest” a Chinese man flees with two birds he has stolen. A gun-toting white man is in pursuit. In the bottom right panel, The Wasp lampoons the Chinese immigrant’s attempt to assimilate as ridiculous, and attempts to “raise the specter of miscegenation.” The panel shows “white woman with a Chinese husband and Chinese children” (Paddison 528). Keller refers to Reverends Gibson and Loomis in his captions as “charlatanical [sic] divines” (West 129).

There are contradictions in the image, however. The male chasing the woman is not dressed in the same dirty, tattered clothing seen at top right. The three gaunt men eat from bowls while rodents scamper on the floor, presumably their next meal, but the immigrant thief shown bottom left is stealing chickens. Why pilfer poultry when a free, plentiful supply of rats and mice were available? This first attempt falls short in consistency compared to the anti-Chinese messages that would be finessed in later Keller images.

[1] The entire testimony can be found at Internet Archive.org

http://www.archive.org/stream/chineseimmigrati00cali/chineseimmigrati00cali_djvu.txt

[2] Joshua Paddison provides a thorough examination of anti-Irish Catholic tensions between Protestant nativism in San Francisco, similar to the tensions among Protestants, Republicans, and Democrats in New York City. Paddison examines early anti-Irish racism in California and how the Irish exploited the Chinese to counteract that racism – capitalizing on labor competition as a means to unite and to assert their place as white men alongside the vast majority of Christian Caucasians who wanted the Chinese driven out.