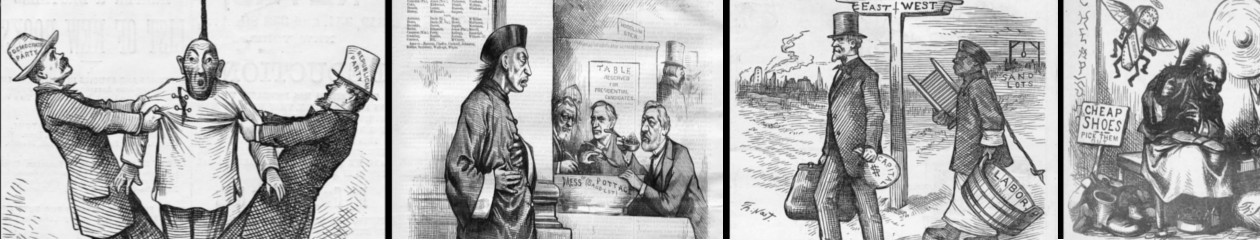

A direct contrast of how the American East and West coast differed toward the Chinese, and other immigrant groups, is shown in two illustrations of an American holiday, both titled Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner. These two cartoons demonstrate how a.) influential Harper’s Weekly was as a publication across the entire nation and b.) how differently these regions approached the issue of immigration and communicated their opinions to their audience. (Double-click images to enlarge viewing).

In 1863, Lincoln proclaimed that Thanksgiving would be celebrated on the fourth Thursday in November. However, the Civil War interrupted national observance of the holiday as southern resentment lingered, preventing old Lincoln adversaries from fully accepting the proclamation. Nast’s Thanksgiving illustration was published one year before it became a national holiday in widespread practice.

Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner, 20 November 1869, by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, Source: Library of Congress

Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner, 20 November 1869, by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, Source: Library of CongressNast’s large woodcut encapsulates the artist’s Radical Republican vision of America after the Civil War. “Nast, Harper’s Weekly and the Republicans they represented did not or could not acknowledge the value of different cognitive, verbal, and social styles, or the sociology behind those differences. They assumed that a universal standard of civility was both natural and necessary” (Hills 118). Nast forms this ideal into an all-inclusive American feast. In the lower corners the sentiments, “Come One Come All,” and “Free and Equal” set the inclusive tone.

At the head of the table is Uncle Sam. He carves a large turkey while an array of nationalities and immigrants politely wait to be served. Universal suffrage and self-governance are featured as the decorative centerpiece. On the back wall, Nast includes his heroes Lincoln and Grant, who flank a center portrait of George Washington, framed by Liberty and Justice. At the table, opposite the host, is Columbia, Nast’s favorite personification of America’s values and promise. Columbia’s kindly face is turned toward her Chinese male guest and his wife and child. It is a very unusual scene since most Chinese in America were men whose families remained in China.

Rounding out the holiday banquet are representatives of an array of races and religions waiting patiently to begin the feast. The work is more an illustration than an editorial cartoon, the genre from which Nast would later earn international fame with his caricatures of William M. Tweed. Only the Irishman exhibits any hint of mild caricature that could be seen as derogatory. Nast would become highly critical of Irish Americans, but he includes an Irish couple as deserving guests. Nast includes the stereotype to make clear to his audience of Protestant Americans, that Irish Americans had right to be at the table. Nast does not draw the Irishman’s wife in “Bridget” caricature and she is attractive.[1] Babies speckle the drawing. This is a family portrait.

Rounding out the holiday banquet are representatives of an array of races and religions waiting patiently to begin the feast. The work is more an illustration than an editorial cartoon, the genre from which Nast would later earn international fame with his caricatures of William M. Tweed. Only the Irishman exhibits any hint of mild caricature that could be seen as derogatory. Nast would become highly critical of Irish Americans, but he includes an Irish couple as deserving guests. Nast includes the stereotype to make clear to his audience of Protestant Americans, that Irish Americans had right to be at the table. Nast does not draw the Irishman’s wife in “Bridget” caricature and she is attractive.[1] Babies speckle the drawing. This is a family portrait.

The guests represent many races and ethnicities and they dine at the table as equals. Nast does not insert them as mere tokens. He imbues them with respect and dignity. They are people capable of relationships and human emotion. The guests at this American banquet are all different, yet bounded by their common humanity.

Covered dishes everywhere wait to be unveiled. At America’s table, there is enough for all to be served. Behind Uncle Sam is a large painting titled “Welcome” which depicts Castle Garden, the processing center for all immigrants in New York City at the time.

This image represents Nast’s true political, utopian philosophy —his belief in a united America and the potential for the nation’s promise.

In 1877, eight years after Nast’s work, George Frederick Keller produced an identically titled cartoon, undoubtedly a direct spoof of Nast’s holiday illustration. This tattered example (the only apparent extant copy) is seen below:

Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving, by G. F. Keller, San Francisco Wasp. Library of Congress, Collection: The Chinese in California 1877

Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving, by G. F. Keller, San Francisco Wasp. Library of Congress, Collection: The Chinese in California 1877The two artists differed in the power and autonomy their editors extended. By 1869, Nast had become a local celebrity and enjoyed little editorial oversight. Unencumbered by owner/general editor Fletcher Harper (much to the chagrin of Harper’s news editor George Curtis who wanted more artistic control) Nast created his images with free artistic rein.

It is generally accepted among Nast and Harper’s scholars that Nast’s images reflected his personal beliefs rather than a directive from his editors or publishers. Richard West has suggested that The San Francisco Wasp artist G.F. Keller only drew what he was assigned. The fact is, little is known about the artist’s political feelings and there is no indication that Keller had the editorial impunity that Nast enjoyed.

Keller’s image includes several international cultures present at the holiday table. Each male guest at the table is feasting upon his national dish, indicating a refusal to assimilate. There are no wives and children joining them.

joy Keller’s Chinese man dines on a rat

joy Keller’s Chinese man dines on a ratFront and center, a tweedy Englishman with long sideburns and hand-held spectacles is aghast as he watches a Chinese man dine on a rat.

Columbia, wearing the outfit of a cook, sassily stands at the threshold of the kitchen and dining room. As a foil to Nast’s Columbine embodying American values, Keller faintly draws his maternal symbol. No one is dining on the same food. Hats of many countries dangle from hooks on the wall. A very racialized African American butler preens as he serves Uncle Sam the holiday meal —the turkey. Interestingly, it is not cooked, indicating a lack of civilization and raw hunger. Uncle Sam represents the California view of the ruling Republican government, which clearly prefers the company of barbarians. Keller’s Uncle Sam leans back, utensils at the ready, eager to dig into his bird. The holiday meal and celebratory experiences are not shared at this table.

A throng of nationalities and ethnicities assembles at the dining room’s entry. A man, possibly a Spaniard matador, stretches out his arms to tentatively hold back invading dinner guests which include Eskimos, more Chinese and men wearing unusual headwear representing other cultures. The matador triumphantly raises his montera in the air! The crowd behind him will soon break through. This Thanksgiving Dinner will soon be enveloped in chaos.

Unlike the Nast drawing, where everyone waits until Uncle Sam carves the turkey, here the guests dig into their own individual feasts. No one is waiting for the host to start. They have no manners. They possess no decorum. The message is clear: it is a mistake to include these outsiders at America’s table.

Harper’s enjoyed a national circulation. The San Francisco Wasp catered to the proclivities and prejudices of its local readership. Wasp historian Richard West writes that there is little evidence that The Wasp was distributed east of the Rockies, though a few issues must have been transported by long distance readers. Nast’s comings and goings were documented in California newspapers. As Nast’s popularity and celebrity grew, other artists, including those employed at The Wasp, enjoyed poking fun of Nast in caricature. Eight years after Nast drew his utopian drawing of an all inclusive America, The Wasp responded with its own version.

[1] The prevailing Irish stereotype in New York was of lower-class, monkey-faced simpleton. Nast likely employed the slightly simian look in this work because his audience would not have been able to distinguish the Irish from the English without the stereotype. This was one of Nast’s kinder renditions of the Irish. His animosity toward the Irish would be developed or artistically realized when New York politics saw a larger Irish role.

2. For a very fine account and amazing examples of The Wasp illustrations, I recommend Richard West’s book The San Francisco Wasp An Illustrated History. It is a must have for anyone interested in political art or nineteenth century cartooning and illustrations. West remains the definitive historian on The Wasp and he is often cited in many scholarly works on editorial cartooning, including Nast.