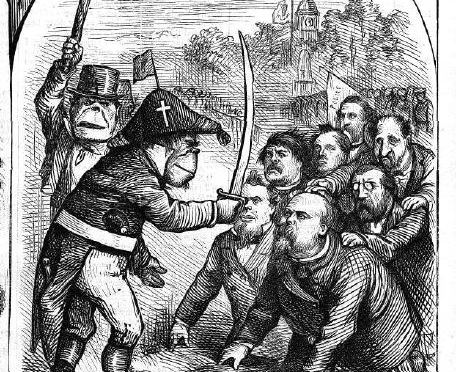

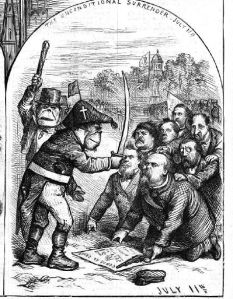

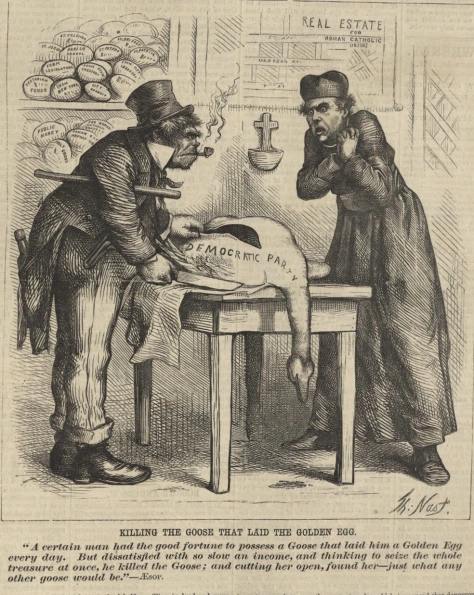

Killing the Goose That Laid the Golden Egg, by Thomas Nast, 11 November 1871. Harper’s Weekly. Source: Museum of Fine Art Houston via public domain license

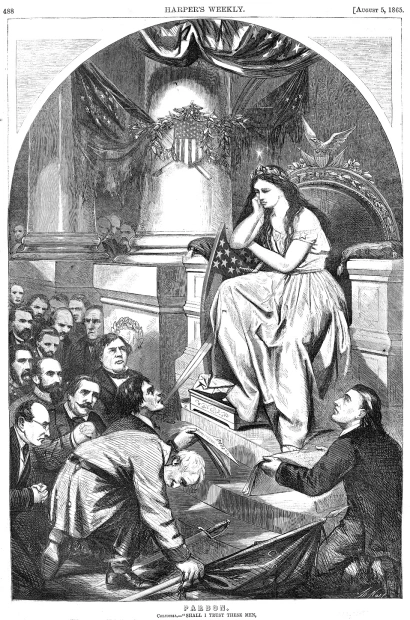

Killing the Goose That Laid the Golden Egg, by Thomas Nast, 11 November 1871. Harper’s Weekly. Source: Museum of Fine Art Houston via public domain licenseNegative Irish stereotypes depicting the Irish as beasts or apes prevailed in an antebellum Anglo-America and anti-Irish sentiments permeated throughout the lives of ordinary Americans, not just neophyte nativists. Historian Dale Knobel, in Paddy and the Republic, examined the culture of language in everyday American life, taking into account the personal correspondence, political speeches, textbooks, travel literature, newspaper, and magazines, songs, theater and novels that were read, discussed and exchanged.

Knobel discovered that negative attitudes toward the Irish existed in America and were expressed throughout the course of everyday life and strengthened as the Civil War approached, a period where his research concludes.

Considering the Irish in America as “outsiders” rather than “insiders” manifested how Protestant nativists weighed immigrant identity and eligibility as Americans in the early and mid-nineteenth century.

Acceptance as potential citizen material depended primarily on race, religion and political character. As the Great Famine migrations progressed toward America, attitudes about the Irish coalesced into a stereotype known as “Paddy” and his female equivalent “Bridget” and Knobel argues that their creation “was a collection of adjectives applied over and over again to the Irish in Americans’ ordinary conversation. This is the authentic definition of a stereotype” (11).

Long before Thomas Nast came to America in 1846, “Paddy” had been well established and “no mere accumulation of random references” (17). Early Paddy stereotypes drew from perceptions of personal character. Although kinder language did surface in Knobel’s surveys of content material, words like “pugnacious,” “quarrelsome,” “impudent,” “impertinent,” “ignorant,” “wickedness,” “vicious,” and “reckless” accumulate as a frequent part of the American lexicon as it related to Irish Americans.

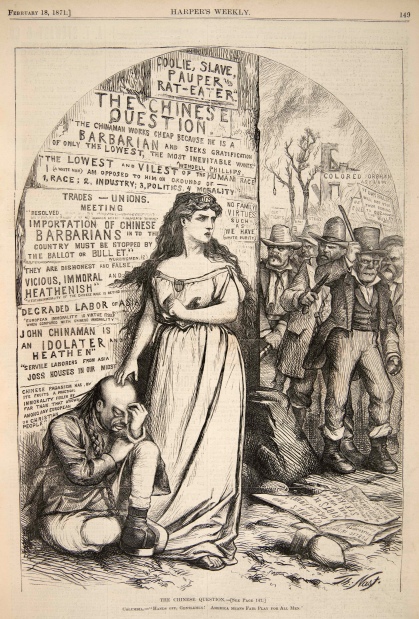

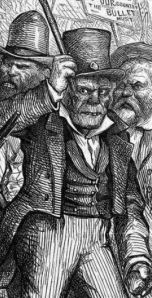

Nast’s Irish thug, From “The Chinese Question” Source: Walfred/UDel Scan

Nast’s Irish thug, From “The Chinese Question” Source: Walfred/UDel ScanAs the nineteenth century turned past its midpoint, Knobel uncovered a marked change in references to physical descriptions of the Irish over describing their character. Descriptors like “ragged,” “lowbrow,” “brutish,” “wild-looking,” and “course-haired” began to surface more frequently. Knobel’s most fascinating revelation observed that in everyday situations in antebellum New York, Anglo-Americans experienced many opportunities to personally encounter the Irish, especially as servants and peddlers.

In Protestant conversations with the Irish and among each other, “words propagated an image of the Irish and thus an attitude” and became a source of judgment. Even if they did not have these occasions to meet an Irish in person, certain assumptions were made and believed to be true, because Americans had become accustomed to believing them (15-16).

Knobel cautions against the inclination to only blame American nativism for anti-Irish sentiment in mid-nineteenth century America. While Knobel’s primary focus was establishing the locations and frequency of words that formed to shape American attitudes and stereotypes of the Irish, he is correct that these words and the mental images that went along with them were enhanced by visual representation such as stage performances and by cartoons.

These portrayals and images helped to establish what antebellum New Yorkers likely thought and considered as fact in forming opinions about the Irish. Thomas Nast came to age in this hegemony and like other artists of his time continued the tradition. Therefore, before delving into Nast’s attitudes toward the Irish, all the while keeping in mind Knobel’s argument, it is useful to look into the origins of the stereotype, which originated in Great Britain.

The Irish-as-ape-stereotype frequently surfaces as a popular trope with the English in the mid-nineteenth century. But, In Nothing But the Same Old Story, researcher Liz Curtis provides plentiful examples that establish anti-Irish sentiment as a centuries-long tradition.

Dehumanizing the Irish by drawing them as beasts or primates served as a convenient technique for any conquering power, and it made perfect sense for an English empire intent on placing Ireland and its people under its jurisdiction and control. The English needed to prove the backwardness of the Irish to justify their colonization (16). When the Irish fought back against English oppression, their violence only perpetuated the “violent beast” prejudice held against them.

James Gillray “United Irishmen in Training” 1798, Source: npg.org.uk

James Gillray “United Irishmen in Training” 1798, Source: npg.org.ukEnglish artist James Gillray painted the Irish as an ogre – a type of humanoid beast – in a reaction to the Irish’s short-lived rebellion against England in 1798. Even before English scientific circles had begun to distort Darwin’s On the Origin of the Species later in the century, the English favored the monkey and ape as the symbols for Hibernians.

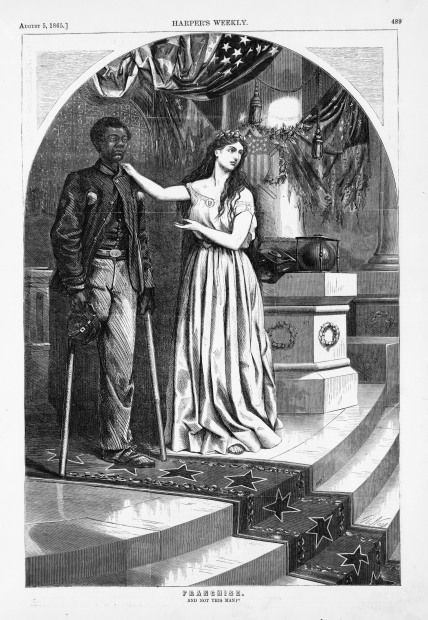

After the Irish made great social and political gains in the latter part of the nineteenth century, the view that they represented a different race (other than other white Europeans) continued to persist as can be seen by this cartoon printed in Harper’s Weekly as late as 1899 (not drawn by Nast):

Harper’s Weekly, 1899. Artist Unknown, Misusing Darwin’s science theories as a basis, the idea of the Irish as less than fully white persisted. This 1899 cartoon showing the Irish stereotype as less evolved, presented as scientific fact 11 years after Nast’s last cartoon was published by Harper’s. Source: Wikipedia Commons

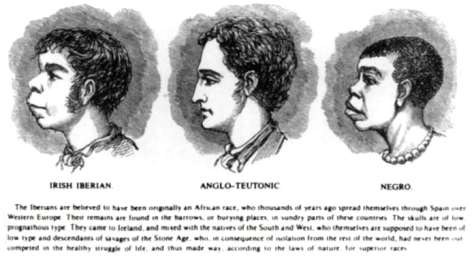

Harper’s Weekly, 1899. Artist Unknown, Misusing Darwin’s science theories as a basis, the idea of the Irish as less than fully white persisted. This 1899 cartoon showing the Irish stereotype as less evolved, presented as scientific fact 11 years after Nast’s last cartoon was published by Harper’s. Source: Wikipedia CommonsBelief in emerging eugenics also emboldened a place for white European superiority. New York brothers Orson Squire Fowler and Lorenzo Niles Fowler, pioneers of phrenology a type of science based on head measurements, touted a philosophy and pseudo-scientific method that rated human intelligence and placement on an evolutionary scale based on the favorable or unfavorable measurements of one’s head. They opened shop in Manhattan in 1835 measuring or “reading” people’s skulls.

This ad for phrenological services was placed in Harper’s Weekly in 1868 Source: Walfred/UD Scan

This ad for phrenological services was placed in Harper’s Weekly in 1868 Source: Walfred/UD ScanThe Fowlers published several books and manuals on scientific methods of identifying, establishing and securing one’s (white people) superior place in society. The size and shape of the skull and forehead were thought to be indicators of “racial-biological differences” (Tchen 148). The Fowlers and their followers believed the assumption that “skulls divergent from the shape of certain northern and western European types were automatically of a lower order” (Tchen 148).

Nast too, was keen to get his cranium measured and examined. “Like so many nineteenth-century Americans, Nast believed that genetic heritage, national characteristics, personal qualities, and achievements all manifested themselves in the physical body” (Halloran 51). No one it seemed, questioned the science of the day.

Leach, John. “The British Lion and the Irish Monkey”. Punch, 8 Apr. 1848. Website: http://adminstaff.vassar.edu/sttaylor/FAMINE/Punch/YI/IrishMonkey.gif

Leach, John. “The British Lion and the Irish Monkey”. Punch, 8 Apr. 1848. Website: http://adminstaff.vassar.edu/sttaylor/FAMINE/Punch/YI/IrishMonkey.gifIn Punch, a popular English weekly illustrated magazine (1841-2002) anti-Irish cartoons were common. In TheBritish Lion and the Irish Monkey, (April 8, 1848) artist John Leach created a tiny monkey (Ireland) who faces a majestic, regal lion (Great Britain). Why a monkey, and not another animal to serve as the preferred animal symbol? The size of the monkey poses no threat to the regal lion. The monkey would have been familiar to the public as a circus or organ grinder’s companion – a demure creature easily trained and controlled. This monkey wears a court jester’s hat. Clearly, to the British literati and readers of Punch, the Irish are a joke. However, the use of the elfin monkey to depict the Irish is less common than the use of an ape.

The ape could be understood as human-like, particularly in terms of Darwin’s emerging theory of evolution, yet inferior to humans. A beast that could encapsulate rough, unsophisticated behavior conveniently attributed to the Irish. Ape-like features assigned to the Irish soon became the ideal stereotype to emphasize the perceived beastly and violent nature of the Irish.

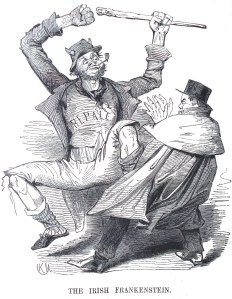

Irish Frankenstein. by Joseph Kenny Meadows. Punch 1943. Irish attempts to Repeal British Union. Note, “repeal” is spelled incorrectly http://www.Punch.photoseller.com

Irish Frankenstein. by Joseph Kenny Meadows. Punch 1943. Irish attempts to Repeal British Union. Note, “repeal” is spelled incorrectly http://www.Punch.photoseller.comAs early as 1842, Punch’s artists “drew on popular notions of physiognomy that the angularity of a face connoted a lower stage of evolutionary development” (Justice 177) and they adopted the practice to depict the Irish consistently in derogatory terms. A Frankenstein monster, seen left, represents Catholic political activism and protests for emancipation, home rule and repeal of the British Union. Under the leadership of charismatic, nationalist Irish leaders like Daniel O’Connell, Ireland’s Catholic peasants were emboldened to demand change. Punch quickly and effectively shut down these aspirations with ridicule.

Irish as ape stereotype – Punch Magazine, 02 February 1849. By John Leech

Irish as ape stereotype – Punch Magazine, 02 February 1849. By John LeechAnimalistic dehumanization was only one of many techniques designed to oppress the Irish and deny them full, human consideration. By regarding the Irish as an “other” the dominant English society could justify and guiltlessly ignore the repercussions of their oppression and cruelty toward the Irish. Watching the Irish starve during the Great Potato Famine Hunger was one manifestation of this belief system.

During the height of the Great Famine, Punch published the English Labourer’s Burden (Feb. 24, 1849) complaining on behalf of England’s outlay of ₤50,000 of famine relief, given to silence Irish protest and demands for assistance.

The Irishman is depicted as a gruff simpleton, getting a free ride on the back of an ordinary English laborer. The English government displayed little sympathy or compassion for the Irish or their famine–related predicaments and despair.

Numerous objections to the Irish proliferated in America as well. Like the English, American Protestants viewed Irish Catholics as “a separate people” (Heuston 82). Irish-American historian Timothy Meagher agrees. “The new Irish American was Catholic. Irish Protestants began melting away into the broader Protestant mainstream” making an effort to vehemently distinguish themselves from the Catholic Irish and preferring to define themselves as Scotch-Irish. See Orangeman’s Riots.

“Most Protestants in America by this time had abandoned the definition of “Irishmen” in order to distance themselves from the Irish Catholic (295). The feeling was mutual.

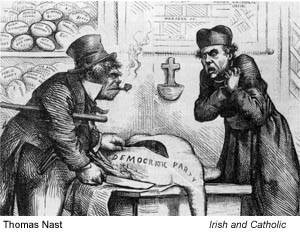

Irish Catholics saw themselves differently from Protestants and, as an embattled people, “in competition with and fighting against all Protestants, Irish or otherwise.” In New York, politician William M. “Boss Tweed” seeking votes, helped the Irish Catholics gain legitimacy and this alliance of Irish Catholics, Tweed and Democratic politics propelled Nast to attack.

Nast was also deeply influenced by the cartoons of English artist John Tenniel who drew for Punch. Tenniel enjoyed star status as Punch’s lead illustrator for several decades. Tenniel was a renown figure, who received high praise for his illustrations of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. He was later knighted and enjoyed a privileged life in England.

According to Nast’s biographer Albert Bigelow Paine, Nast and his colleagues at Harper’s Weekly were keenly aware of what other artists abroad were drawing, particularly at Punch. Nast had access to John Tenniel’s snarling, aggressive, simian-faced Irishmen (28). Nast borrowed heavily from Tenniel both in concept and technique. A startling example of Tenniel’s effect on Nast’s art can be seen in the following two cartoons, first Tenniel’s and then Nast’s. Compare:

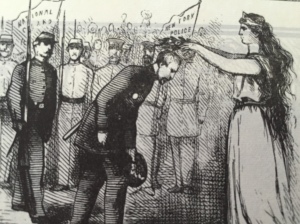

John Tenniel drew this Guy Fawkes for Punch on 28 December 1867. Tenniel was a major influence on Nast when the latter moved into a caricature for Harper’s Weekly.

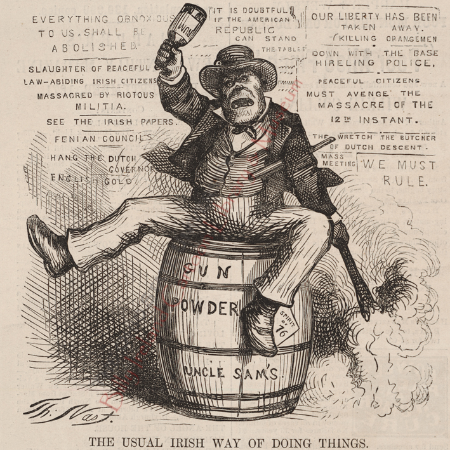

John Tenniel drew this Guy Fawkes for Punch on 28 December 1867. Tenniel was a major influence on Nast when the latter moved into a caricature for Harper’s Weekly. Nast heavily borrowed from Tenniel’s 1867 cartoon to create his American version of an Irish-Catholic scandal. Nast called out hypocrisy when the Catholic Irish rioted to protest Protestant Irish’s right to parade in New York City. Whether once sees this cartoon as effective or offensive, Nast’s visual attack could hardly be called “original.” The Usual Way of Doing Things, by Thomas Nast, 1871. Source: The Ohio State University.

Nast heavily borrowed from Tenniel’s 1867 cartoon to create his American version of an Irish-Catholic scandal. Nast called out hypocrisy when the Catholic Irish rioted to protest Protestant Irish’s right to parade in New York City. Whether once sees this cartoon as effective or offensive, Nast’s visual attack could hardly be called “original.” The Usual Way of Doing Things, by Thomas Nast, 1871. Source: The Ohio State University.Today, the name Thomas Nast bears a particular infamy among American Irish Catholics. His body of anti-Catholic and anti-Irish work is quite substantial and brutal. Nast’s reasons for attacking Irish Catholics directly deserve a closer look. His cartoons resulted from his perception of four issues which demanded response through his visual commentary:

- 1.) Irish Catholics relationship with William M. “Boss” Tweed – and the many issues that stemmed from that alliance,

- 2.) The role of the Catholic Church (thereby Irish) involvement in the New York Public School controversy (also involving Tweed),

- 3.) American Roman Catholic Church and Democratic Party’s stance against abolition, and lastly,

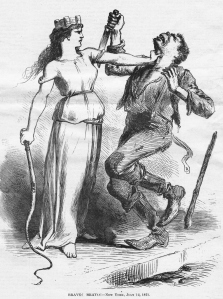

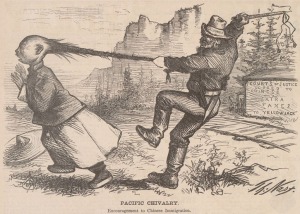

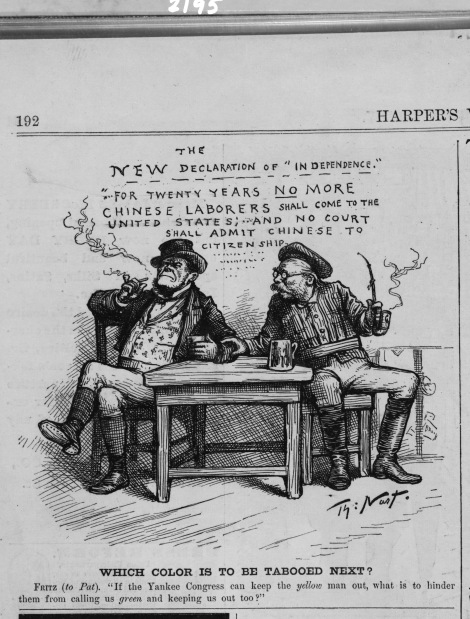

- 4.) Irish-Democrats pro-labor violence against Chinese immigrants.

Whether Nast was justified in his decision to attack Irish-Catholics is complicated. Today, modern sensibilities judge Nast quite harshly. For these reasons, he remains the subject of passionate debate. These images must be weighed against other cartoons where Nast drew positive images of the Irish, but these representations often blend into the background. Modern lobbying efforts to keep Nast out of the New Jersey Hall of Fame have so far been successful.