Opinion:

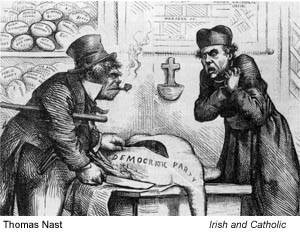

In October 2011, Thomas Nast, (1840-1902) appeared among a list of distinguished individuals nominated again for induction into The New Jersey Hall of Fame. The nomination, Nast’s third in four years, would not result in his induction. Despite Nast’s legacy as the “Father of the American Caricature” (Harper’s Weekly, Dec. 20, 1902), the accolades and fame earned for his series of approximately 50 cartoons exposing the corrupt New York City Tammany Hall boss William Meager Tweed would not be enough. Rather, it would be another Nast legacy, his anti-Irish and anti-Catholic cartoons drawn primarily in the late-1860s to mid-1870s, which determined Nast’s failure to be included in the Hall of Fame roster.

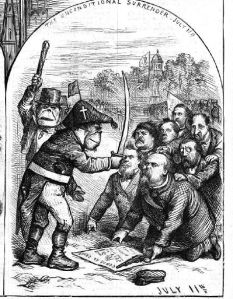

Caricature can be a cruel expression of contempt. Cartoon historians Stephen Hess and Milton Kaplan refer to caricature as the Ungentlemanly Art; Donald Dewey, the Art of Ill Will. As an editorial caricaturist, Nast relied on techniques to exaggerate physical features, employ personal ridicule, symbolism, and stereotype to expose what he saw as “a struggle between good and evil” (Dewey 7). Nast viewed Irish Americans and the Catholic Church in the post-Civil War era as direct threats to the Republican values of inclusion, unity, toleration, and fairness. He saw the rise of Tweed’s Democratic Tammany Hall Ring, the Irish immigrants, and American Roman Catholics as inexorably linked, one group enabling the others’ prominence.

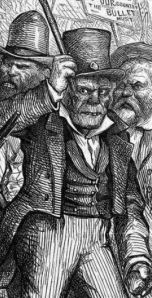

Nearly a century and a half after they were drawn, Nast’s Irish and Catholic depictions continue to deeply offend. Reprising an English tradition of depicting the Irish as beasts, most typically as apes, Nast’s Irish was a brutish, violent- loving, jaw-jutting aggressor.

Nast, who was born and baptized in the Catholic faith, and received early Catholic education, frequently drew sinister-looking Catholic clergy, usually elaborately robed and surrounded by riches. Recently, these images have resurfaced as a retort to Nast’s 2011 Hall of Fame nomination. The cartoons appear in numerous blogs and editorials – examples offered to prove that Thomas Nast was a racist and a bigot. These images should not be viewed in isolation, without historical context to explain their purpose.

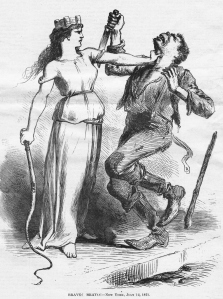

Thomas Nast had a well-established history of supporting fairness and equity, but he would quickly attack those he had previously championed when he perceived hypocrisy, corruption or stupidity within the ranks of previous favorites. Nast’s most famous targets: Tweed and the Irish-Americans Catholics who affiliated with and benefited from the political boss, had questionable alliances and political stances. As emerging actors in New York City Democratic politics, Irish-American Catholics under Tweed’s protection provided a critical backdrop in which a six-year-old Catholic immigrant from Germany came of age, and formed a political identity. Nast witnessed extraordinary characters and cultures, indeed he was part of New York City’s immigrant identity. As Nast matured in this cultural and political soup, he found a passionate solidarity within the progressive politics of the new Republican Party. In particular, after the Civil War, Nast identified his enemies as Democrats and their positions on key social and political issues fueled the ire in his ink.

Nast critics deserve a hearing, however. For example, in his 1863 Emancipation drawing, Nast took great effort to present an optimistic vision of African Americans contrasted against a reminder of African American slavery and oppression. It was important for Nast to present the two together. But when it came to the Irish-American experience, Nast did not explore or comment on the Irish’s long history of oppression in Europe. Nast appears not to have considered any background material which could have furthered his understanding of their collective behavior in America. His work is not sympathetic to the Irish’s dire living conditions in New York City. Nast may have shared a common attitude held by most Germans Americans that they superior to the Irish.

If Nast felt superior, he was not alone. Dale Knobel explains that the rank and file Americans, prior to the war at least, believed that environment was a direct result of a defect in character – in this case, the native Irish character, and character developed from one’s environment. The prevailing view among Protestant Americans held that the Irish had made poor life decisions (marrying early, too many children, following a pope and superstitious religion) and therefore deserved their troubled lot in life (82). Irish-American historian Timothy Meagher writes that Ireland’s troubled history is often overlooked when explaining subsequent Irish American behavior. The Irish didn’t act like Germans because “they were from Ireland and had learned “lessons” there that shaped their reaction” to other races religions and cultures (224).

Had Nast fully studied and appreciated the Irish’s history of oppression and the extraordinary circumstances that caused them to emigrate to America, would he have excused the intertwined relationship of Irish Catholics with Tweed? Probably not. As sympathetic as he was to African Americans, Nast later resorted to racial caricatures and lampooned African Americans when they (in Nast’s opinion) too easily gave away new civil rights gains in the early days of the Restoration. Nast felt they hurridly compromised with southern Democratic politicians — a ruling class Nast felt to to be insincere and corrupt.

Blacks, who Nast once drew with dignity and respect, later became guffawing simpletons who didn’t know better — incapable of navigating through the complex and murky waters of southern politics. As tender as Nast could be in an image like Emancipation, he could be unmerciful in his treatment of minorities in images like The Ignorant Vote. These depictions couldn’t be any more inconsistent.

Albert Bigelow Paine, (1861-1937) was Nast’s only contemporary biographer and penned a reverential 600-page tome published two years after Nast’s death. Paine interviewed Nast toward the end of his life, and he does not challenge the recollections of his subject and the anti-Irish and anti-Catholic drawings are weakly examined.

In an effort to explain away the anti-Catholic reputation that had obviously lingered and threatened to tarnish Nast’s legacy, Paine wrote, “He was inspired by no antagonism to any church–indeed he was always attracted by Catholic forms and ceremonies” (150).

Extraordinary and divisive national events shaped Nast’s persona and outlook. In his adopted country, Nast embraced and championed a Republican political view — a position reinforced by his employers at Harper’s Weekly and the at-large intelligentsia of the day. His attitudes about the Irish were not at all unusual. This was the era when “Irish Need Not Apply” signs proliferated across storefronts and businesses. Knobel’s convincing research makes this very clear. In this atmosphere of an evolving America, Nast transitioned from an illustrator to a caricaturist; the latter’s prime purpose was to expose, within his immediate environment, malfeasance, corruption, lapses in morality, etc. To be successful and effective as a visual commentator and observer, his caricature needed to shock and startle. Caricature provokes and elicits conversation and debate.

In using caricature, Nast purposely fired a weapon clearly meant to exaggerate, upset, and call attention to a specific issue or crime. Exaggeration was precisely his point. Nast argued for diversity and illustrated these differences with recognizable symbols his readers would immediately grasp — an artist’s version of shorthand.

How would Nast have drawn a positive image of an Irishman? Perhaps he did, and these white, Euro-centric faces simply blend in. How would we recognize a positive Nast Irishman if he did not use stereotype? Wouldn’t the Irish look like any other Anglo-American? When something was wrong, went wrong,, Nast drew out his pen and pencil and fired off an attack. The Irish and Catholic alliance with Tweed and the growth of their political prominence and activism (including adopting a pro-slavery political position) provided the fodder — the examples for Nast to run with his preconceptions.

In his book the Irish stereotype, Paddy and the Republic, Dale Knobel quotes Harold Lasswell, a content analyst who helped compile period material for the book,

It is impossible to get inside the mind and observe attitude as one might observe conduct. We obtain insight into the world of the other person when we are fully aware of what has come to his attention (qtd. Knobel xv).

When one browses the Internet and grabs one of Nast’s drawings do we know the full story? Nast drew more than 2,200 cartoons for Harper’s Weekly (Kennedy) alone. A vast majority of his images focused on the people, groups, and religion of my Irish ancestors. In these pieces, I see a slice of history as it was, not how I wish it would have been! His images are historic and possess intrinsic value. Nast came of age during events, controversies, drama, and a cascade of cultures. In order to assess the layers of meaning, and do it with justice, involves an extraordinary commitment of time and affection for history. To fairly evaluate these documents (and Nast’s images) involves having an open mind and a curious nature willing to explore the many backstories and cultures that shaped individual attitudes and behavior during Nast’s career. Every detail — the meaning behind every symbol, the tradition and origin of each stereotype, and the significance of the words, placards, and captions that accompany his caricatures all play a vital role in understanding these cartoons.

When one browses the Internet and grabs one of Nast’s drawings do we know the full story? Nast drew more than 2,200 cartoons for Harper’s Weekly (Kennedy) alone. A vast majority of his images focused on the people, groups, and religion of my Irish ancestors. In these pieces, I see a slice of history as it was, not how I wish it would have been! His images are historic and possess intrinsic value. Nast came of age during events, controversies, drama, and a cascade of cultures. In order to assess the layers of meaning, and do it with justice, involves an extraordinary commitment of time and affection for history. To fairly evaluate these documents (and Nast’s images) involves having an open mind and a curious nature willing to explore the many backstories and cultures that shaped individual attitudes and behavior during Nast’s career. Every detail — the meaning behind every symbol, the tradition and origin of each stereotype, and the significance of the words, placards, and captions that accompany his caricatures all play a vital role in understanding these cartoons.

Caricature and editorial cartoons go beyond mere illustration. Simple illustration captures the obvious action along with the ingredients that everyone recognizes. Caricature captures an unseen truth — a truth exposed, an opinion perhaps, that many would prefer to brush under the carpet. Caricature peels back the layers of illusion and exposes a starker reality.

Had it not been for particular political alliances, which in Nast’s view involved stolen elections, misappropriated public funds, and an enormity of ego and arrogance, there would have been few reasons for Nast to have attacked Irish Catholics. Every line Nast drew, he executed toward achieving or arguing for a Republican political view. One may not agree with Nast’s political thinking, but those who are informed about his life and times find it difficult to question the well of integrity from with which he drew his creative inspiration and the evidence of corruption that swirled all around him compelled him to take action. See Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner.

Nast took to task the people he saw as villains, and as a result, in the eyes of many, became one himself. Nast did not glamorize the villains and threats of his day. He obliterated them through the exposure of black lines on white paper. As wrong as these perceptions and images might feel today, the truth is, most people felt that way toward the Irish. Because of his ability to visualize the way ordinary Americans felt, Thomas Nast now bears the brunt and identification of owning this attitude lock, stock, and barrel.

Today, Americans with an Irish heritage often react with anger at Nast’s nomination, and may not fully understand nor be willing to accept the knowledge that a sizable portion of our ancestors, horribly oppressed in Ireland, became oppressors in America. Ignorance is bliss. In the Irish-American struggle to fit into mainstream America, other immigrant groups were mistreated, most notably the Chinese, by the Irish and other white groups. In climbing the rung and elevating one’s status from a low life meant another group had to occupy the lower tier. Horrible things were done to the Chinese in caricature and more importantly, in everyday life. In a large part of organized Irish activism, the Chinese faced a battery of restrictive legislation and were officially excluded from immigrating to America with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Historical figures like Nast should not be kept out of museums or halls of fame any more than Mark Twain’s use of the N-word should be erased from modern editions of Huckleberry Finn. Our history is full of unique people who did not all get along. The beginning of the immigration era of American history is complicated, extraordinary and often cruel. Nast deserves to be in New Jersey’s Hall of Fame because he earned a place in history through his exposure of political corruption and for documenting the Civil War, national elections, minority struggles and visually capturing and recording northeastern Republican attitudes of a still young nation seeking to reconcile after the Civil War. His art shaped ideas. Not all of us are going to like what he did, and that is fair, but we can’t pretend it didn’t happen.

Today, Thomas Nast’s controversial images are an important educational tool for explaining how and why images matter, how stereotypes are developed, used or misused. Caricature is not illustration and it is not meant to be viewed as such. It is sarcasm, it is an over-the-top exaggeration. Its very nature is controversial and Nast executed that art form as few others could, and for that reason alone, regardless of content, he deserves a spot in New Jersey’s Hall of Fame.