“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” – George Santayana, “The Life of Reason,” 1905

Donald Trump is not the first presidential candidate to call for the outright exclusion of a group of people, based on ethnicity or religion, from entering the United States as a visitor, or as an immigrant with aspirations for citizenship. That notoriety goes to James G. Blaine, the U.S. Senator from Maine.

In the late nineteenth century, the three-time presidential hopeful sought to make his second attempt in 1880 a shoe-in by pandering to a xenophobic and fearful population of Euro-centric Americans. Blaine sought to abrogate a treaty protecting Chinese immigration. Needing the support of white labor in the west in order to achieve his presidential aspirations, Blaine encouraged their chants of “The Chinese Must Go!” and promised support of their demands.

As an 1880 Republican presidential hopeful James G. Blaine called for the official federal exclusion of Chinese entering the U.S. Fear mongering began soon after the Chinese arrived the United States. America offered hope to immigrants from across the globe, including the Far East. Lured to America with tales of gold nuggets, the Chinese were early arrivals during the Gold Rush. Like the Irish flooding into the East coast, the Chinese sought relief from the famine plaguing their homeland.

And while suspicions percolated about the Irish on the East Coast, by the 1870s, Sinophobia reached fever pitch on the other side of America. Blaine took notice. Readying for another attempt at the presidency, Blaine saw political advantage in aligning alongside a new, burgeoning and fearful electorate. In doing so, Blaine broke with his Republican Party’s tolerant position on accepting the Chinese. Nast found Blaine’s defection unforgivable.

In the late nineteenth century, the Chinese in America as a whole, were viewed as a critical threat to the health, welfare, and security of the United States. Derided for their non-Christian (heathen) ways, the Chinese represented a multi-level threat. Popular rhetoric, steeped in propaganda, flourished.

To white workers, citizens and immigrants alike, a life and death line needed to be drawn! Was there any doubt that the rat-eating Chinese would, and had already, spread life-threatening disease and pestilence among innocent Americans? Despite their modest immigration numbers, statistically low compared to other immigrants, the Chinese were nevertheless depicted in commentary and illustrations as invading hordes of less-than-human creatures who would forever alter and undermine a wholesome American national identity and culture.

The pro-business and progressive Republican Party during this era encouraged the Chinese to come to the U.S. Manufacturing and industry, particularly railroad executives, valued the Chinese work ethic and used their eagerness to work as strike breakers. Despite their strangeness, the Chinese were earnest workers and helped tip many businesses balance sheets to the black. This financial reality bolstered the Republican-led, East Coast ruling elite’s tolerant position toward the Chinese. At the very least, having the Chinese in the U.S. made good business sense.

The Democratic Party thought differently. Echoing the fears of its burgeoning white and Irish labor base, Democrats sought to restrict the Chinese from arriving and wanted the ones already in the U.S. to go. Starting on the West Coast with local laws, talk of national laws excluding the Chinese in the U.S. steady gained acceptance during the 1870s. By 1879, the early drafts of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act had been entered into legislation and although vetoed, marked the beginning of the end for Chinese immigration. The writing was on the wall.

Blaine saw where the future votes were. He needed the western vote to win his White House bid. Blaine called for an end to the Burlingame Treaty, a treaty his Republican party had crafted. Blaine renewed the process to officially ban Chinese immigrants – legislation that made life miserable for the Chinese already in the country legally.

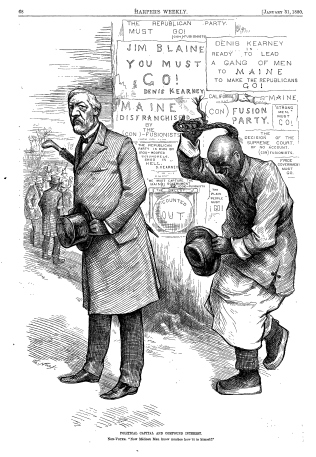

Nast obliterated Blaine for his betrayal of Republican values. With a force reminiscent of his treatment toward Tweed, the German-American artist produced a series of devastating cartoons lampooning Blaine and his hypocrisy. A sampling:

8 March 1879 – “The Civilization of Blaine”

15 March 1879 – “A Matter of Taste”

15 March 1879 – “Blaine Language”

22 March 1879 – “Protecting White Labor”

31 March 1880 – “Political Capitol and Compound Interest”

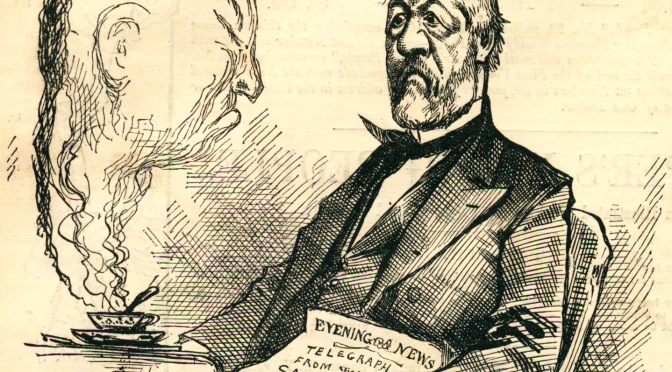

20 March 1880 – “Blaine’s Teas(e)”

1 May 1880 – “Boom! Boom!! Boom!!!”

8 May 1880 – “The “Magnetic” Blaine, or a Very Heavy “Load”-Stone for the Republican Party”

Fully aware of Nast’s role in Tweed’s downfall, Blaine appealed to the artist andHarper’s Weekly General Editor, George W. Curtis, to cease producing the cartoons. Nast’s pen would not be silenced. His cartoons are considered to have played a significant role in Blaine’s unsuccessful presidential bids in 1876, 1880 and 1884. Blaine’s last attempt went as far as earning the Republican nomination.

Blaine’s 1884 campaign, two years after the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act, propelled both Nast and Curtis to shift their allegiance, a small, but vocal group of progressive-leaning Republicans known as “Mugwumps.” By endorsing the Democratic candidate Grover Cleveland on the pages of the venerated, Republican Harper’s, the move was was startling to the Republican establishment and Party of Lincoln. Although it is widely believed that Nast’s excoriation of Blaine cost the politician the presidency, Nast’s move to the Democratic side, albeit on moral grounds, significantly contributed to the cartoonist’s loss of favor with the Republican base and marked the start of his downward trajectory at Harper’s Weekly. Nast could not remain faithful to his party.

As we all know, Blaine did not become president. Blaine lost his battles, but the war against the Chinese was won. Enacted in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act became the first federal legislation to ban outright, a population of people, based solely on ethnicity. Those Chinese already in the United States were prevented from many of the rights extended to other immigrants. They could not vote, were targeted with special taxes, and property rights and ownership were severely restricted. The Chinese in America could not return to their homeland for visits, as their re-entry would be barred, nor could they call for family to join them in the U.S. For the 61 years that the Exclusion Act sat on the books, it effectively and permanently separated Chinese men from their families at home. The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, primarily as a response to the Chinese – American alliance during World War II.