On Monday, December 7, 2015, Bill Bramhall, editorial cartoonist for the New York Daily News published the following image of presidential candidate Donald J. Trump, in response to Trump’s announced policy of denying Muslim immigration to the U.S.

The image was placed on the cover of the daily paper, overlaid by an updated and paraphrased version of Martin Niemöller’s iconic and poignant quote from 1963 about his inaction regarding Adolf Hitler:

The image shows the Statue of Liberty as a victim of Trump’s political terrorism. Lady Liberty, the beloved symbol of American values and immigration, is beheaded. A bloated Trump raises his weapon of choice, a scimitar, historically associated with Eastern and Ottoman cultures. In effect, Trump balances his own scales of justice with her head in his other hand. The remainder of her majestic body lies prostrate, her torch has tumbled away — her welcoming beacon of light is extinguished.

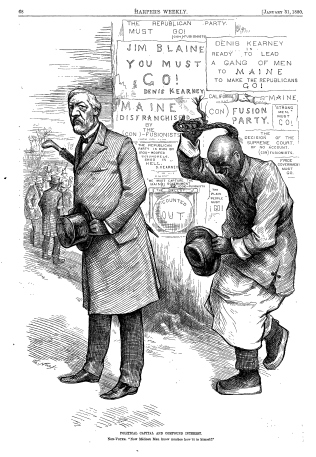

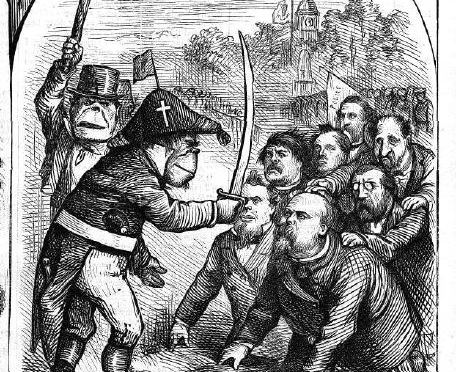

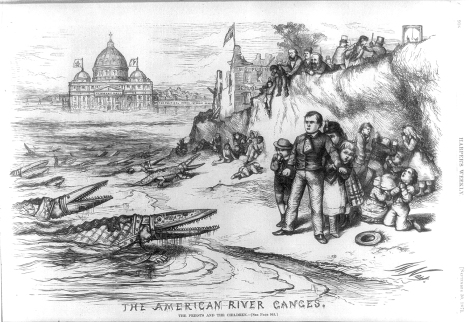

Bramhall’s image brings to mind Thomas Nast’s 1871 double-paged cartoon,”The Tammany Tiger on the Loose – “What are you going to do about it?””

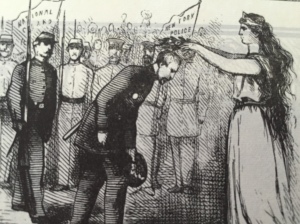

Though not a cover, (many of Nast’s cartoons were featured as covers), this cartoon received an equally coveted double-page spread in the center of Harper’s Weekly, the premier illustrated weekly of its era. A portly Tweed, whom Nast dresses as a Roman emperor, sits in his imperial reviewing box and gloats upon his weapon of choice, the Tammany Tiger as it takes down Columbia, Nast’s preferred personification of American values. Drawn 15 years before the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886, Nast favored Columbia as the maternal symbol to represent the American nation. Her cousins, Lady Liberty and Lady Justice, distinguished by a crested helmet and the scales of justice respectively, appeared less often as substitutions for Columbia, but frequently as sisterly companions.

Tweed’s tiger looks straight into its audience and bears its teeth, poised to tear into Columbia’s neck. Columbia often carried a sword, symbolizing the strength of her resolve to protect American values of tolerance, fairness, and compassion. Her weapon has left her grip, broken apart by the force of the beast’s pounce. Like Tweed, the tiger arrogantly asks, “What are you going to do about it?”

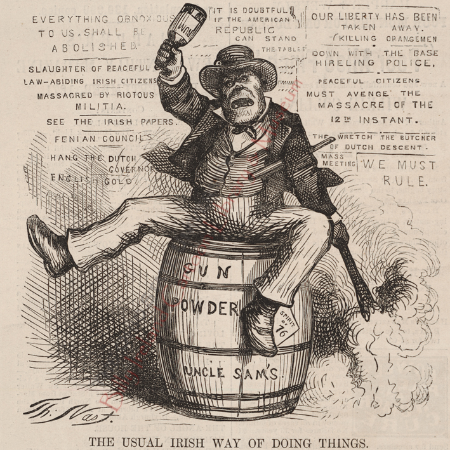

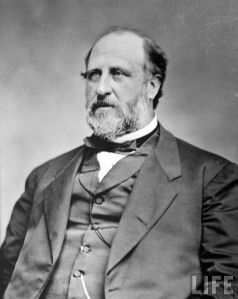

Thomas Nast, known as the “Father of American Caricature” or alternately as the “Father of the American Political Cartoon” rose to worldwide attention and wielded significant political power by the deft and powerful strokes of his pen — the ire in Nast’s ink often appeared on the cover of the illustrated weekly magazine, Harper’s Weekly. To get his message across, Nast and other great cartoonists of the time employed the ego-cutting tools of caricature: ridicule, physical exaggeration, and careful placement of symbols, to elicit emotions from readers and viewers. Nast is best known for excoriating and bringing down New York politician William M. “Boss” Tweed through these techniques. The visibility and power of Nast images continued for two decades as undeniably effective weapons against corruption.

Few escaped seeing Nast’s images. Apocryphally, Tweed is famously quoted as saying, “Stop them damned pictures. I don’t care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing them damned pictures!”

According to Nast’s biographer Alfred Bigelow Paine, Tweed representatives tried to entice Nast with bribes to tempt the artist to stop maligning the city boss. Intrigued, Nast strung the agent along, seeing how high he could negotiate the bribe. It reached $500,000, a tremendous amount of money for its time. Nast refused to be bought.

This The New Yorker cover from 2008 elicited a great deal of conversation and controversy.

This The New Yorker cover from 2008 elicited a great deal of conversation and controversy.The American editorial or political cartoon in the twenty-first century grasps an uncertain future. The genre thrived in Nast’s era, a time in which photographs could not easily be mass reproduced for the print media. In the century that followed, modern political cartoons traditionally found their stage off the front page, yet, placed in a venerated position in the editorial sections of daily and weekly newspapers. The photograph took over on covers. There were exceptions, of course, the New Yorker magazine being the most notable, today giving prominence to the cartoon cover with provoking results.

The tradition of home delivery or buying a paper at a newsstand and enjoying that publication at the kitchen table or office desk— physically leafing the pages and sharing sections among family and friends, assured these editorial cartoons would be seen multiple times over.

With the demise of many print editions of newspapers and magazines, new generations of readers are now able to cherry-pick their news from online offerings. Some fans of the art form fear that these hand-drawn visual commentaries, and appreciation for what Donald Dewey has called The Art of Ill Will, might lose their historic influence, or get lost among the many clickable headlines, losing ground to the altered digital photograph — satire by Photoshop.

Bramhall’s cartoon offers hope that the cartoon caricature is still beloved. It possesses the qualities to pack a powerful punch. Bramhall’s image rose above the fray and was instantly picked up across media outlets and shared prolifically on social media.

The New York Daily News use of Bramhall’s cartoon as its cover, therefore, is in the best tradition of an excellent and scathingly successful takedown of a public figure by an editorial or political cartoon, drawn and delivered, much like Trump’s sword, as a blunt courier of raw truth. In the best New York City media tradition, the cartoon exposes both the disturbing and the ridiculous.

In our saturated and specialized markets, editorial cartoons must compete for broad attention. But when they are timely and deftly drawn, these black and white lines of editorial expression expose stark realities through exaggeration. Ah! To dish out the glorious tool of ridicule, a technique Trump wields with expertise and lately, to great effect.

Like Nast and Bramhall’s cartoons, the crème de la crème of caricature will always rise to the top — viral-worthy, these images and the artists who create them, serve the public good by striking a tender national nerve and provoking us to consider both the obvious and the subtle.

If Nast were around today, he’d be proud, and perhaps, a little envious.